Formats

Long-term Insights Briefings, Policy Stewardship and Futures Thinking: What you need to know#

Government departments have started work on their inaugural Long-term Insights Briefings. The political term, news cycle, and demand for immediate action can focus us as individuals and institutions on the present. Long-term Insights Briefings are intended to balance the scales and carve out more space for long-term thinking.

As individuals, we need to be alert to the tendency to focus on today’s challenges rather than tomorrow’s. Although this positions us well to respond to immediate needs and demands, we also need to prepare for what’s coming over the horizon.

This article sets out what policy advisors need to know about the Briefings and how they fit within broader stewardship requirements and futures thinking. It sets out how we can cultivate stewardship in our policy practice and how the Policy Project’s frameworks, tools and guidance resources can help – both in developing policy that’s fit for the future, as well as fulfilling the requirement to publish a Briefing.

Once the Briefings are published, their long-term insights will be a useful resource that policy advisors can use to look over the horizon, and prepare for tomorrow.

What is stewardship?#

Stewardship means different things in different contexts. In te ao Māori there is the concept of kaitiakitanga. Generally translated as relating to the guardianship or stewardship of natural resources for the benefit of future generations, this is relevant to other matters such as te reo Māori, education and health. The previous Head of the Policy Profession, Andrew Kibblewhite (in his speech In Pursuit of Better Stewardship) has described stewardship as “taking decisions or actions today that mean we are collectively better off in the future than we would otherwise have been”. By its nature, stewardship incorporates a long-term perspective with a view of future risks and opportunities.

As public servants, we have a duty of stewardship. Stewardship is one of five principles enshrined in the Public Service Act 2020 (section 12) that characterise how the public service operates. Public servants are expected to proactively promote stewardship of the public service when going about their work.

The Act also sets out the responsibilities of Chief Executives to their minister (section 52). Chief Executives and those acting on their behalf are responsible for supporting the minister to act as a good steward of the public interest. The Act includes examples of support, such as “maintaining public institutions, assets, and liabilities” and “providing advice on the long-term implications of policies”.

In the policy context, this duty of stewardship also involves looking ahead and providing advice about the future challenges and opportunities New Zealand faces. As well as responding to the priorities of the government of the day, government agencies need to maintain their capability and capacity to support successive governments to develop their policies and pursue the long-term public interest.

How can we cultivate stewardship?#

It sounds simple, but stewardship can be tricky in practice. On a day-to-day basis, the immediate and urgent can crowd out the long term. As well as the challenge of safeguarding resources to conduct longer-term thinking, identifying the focus of stewardship work requires trade-offs and discussion on what matters to the long-term public interest. It involves considering a range of interests and different perspectives.

Policy stewardship typically involves identifying those current issues that haven’t received adequate consideration, as well as new and emerging issues, and making space in the strategic policy work programme to explore these further. This means having the capability and tools to identify those issues that are likely to have significant implications for the long-term public interest. It also means building and maintaining knowledge and expertise on these issues. Doing so equips the public service to provide free and frank advice to current and successive governments.

A stewardship perspective can also be applied when working on an individual policy issue to bring the long-term into more immediate policy work. By being informed of those issues that are likely to be important for the long-term public interest, we can frame and develop our policy advice with an understanding of these broader issues at play. This means have the capability and tools to:

- gather insights on the underlying drivers of change to identify and test assumptions about the future development of the policy area

- test the suitability of the policy intervention in a range of future as well as current conditions

- develop policy advice that is more fit for the future.

To cultivate policy stewardship, we need both the enablers at the policy organisation level and the skills at the individual level. The Policy Project has established what good practice looks like through co-designing the policy improvement frameworks with the policy community.

Policy Capability Framework – organisational level#

The Policy Capability Framework sets out what government agencies with policy functions need to focus on to produce quality policy advice. Stewardship is one of the four components of policy capability. The Framework defines stewardship as a focus on policy outcomes and building capability for the future.

It comprises four elements – leadership and direction, strategy and priorities, culture, and investment in future capability. For each element, there are lead questions and lines of inquiry. The full content for ‘leadership and direction’ and ‘strategy and priorities’ can be found on page 11 of the Policy Capability Framework review tool.

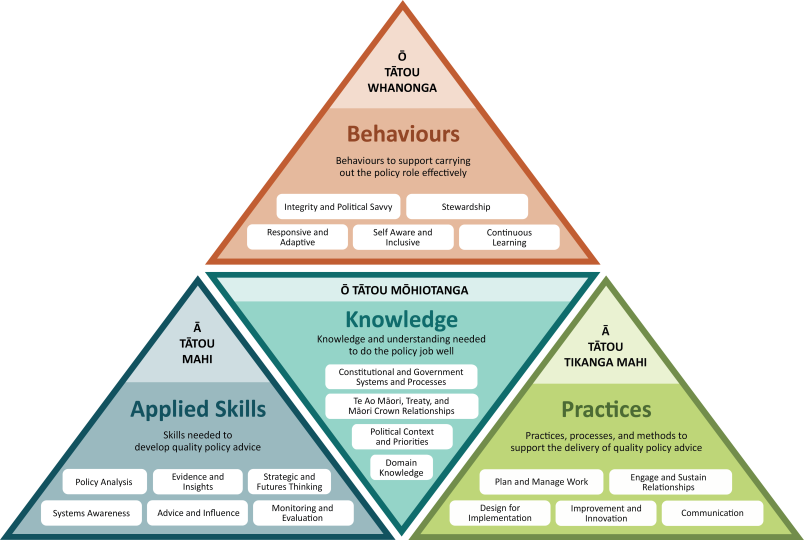

Policy Skills Framework – individual level #

The Policy Skills Framework sets out the knowledge, skills and behaviours policy advisors require to deliver quality policy advice at three levels of competence competence – developing, practising, and leading.

Strategic thinking is one of the applied skills that policy advisors require to deliver quality policy advice. It incorporates the discipline of futures thinking. The description of strategic thinking at the three competency levels can be found on page 21 of the Policy Skills Framework.

How can futures thinking help?#

Futures thinking provides a range of techniques for thinking about the drivers of change that are shaping the future and exploring their implications for today’s decisions. The aim of futures thinking is not to predict the future, but by exploring the range of possible futures be better prepared for what may unfold, test assumptions and make decisions that actively shape the future you want.

There are more than 30 futures techniques. Some of the more commonly used techniques are horizon scanning, assumption testing, scenarios, and futures wheel.

Futures techniques:

- look for signs of change that may shape the range of possible futures

- use diverse data sources (e.g. quantitative and qualitative trends, online literature reviews, stakeholder insights)

- engage with diverse stakeholders who can give their varied experiences to create more robust views on the future

- apply a systems lens to consider the greater factors that may shape the international, domestic and organisational context.

Futures thinking is a discipline in its own right, and is used in strategy development, design and planning, and informing policy development. It can be used to support and enable policy stewardship. Rather than extrapolating the future from the past or projecting current conditions into the future, it considers the range of possible futures and then explores the implications for the present. This brings into focus disruptive change and surprises that could arise.

The Policy Project has guidance on how you can apply futures thinking to the policy process. This contains information about futures thinking, why you should use it, what it involves, the different futures thinking techniques and case studies on how it’s been applied to the policy process.

Where do the Long-term Insights Briefings fit?#

Schedule 6 of the Public Service Act 2020 introduces a new requirement for government departments to publish a Long-term Insights Briefing at least once every three years. The Briefings enhance the requirement for the public service to consider the long-term.

The purpose of the Long-term Insights Briefings is to make publicly available:

- “information about medium and long-term trends, risks and opportunities that affect or may affect New Zealand and New Zealand society

- information and impartial analysis, including policy options for responding to these matters”.

The Briefings are public service think pieces on the future, not government policy. The requirement to publish a Briefing is a statutory duty on departmental Chief Executives, independent of ministers.

The Briefings are an opportunity to enhance public debate on long-term issues and usefully contribute to future decision making. The Act requires departments to seek the community’s feedback at two points – on the proposed topic of the Briefing, and the content and detail of the draft Briefing. This reflects the role the public has in saying what matters for the future of New Zealand and in shaping that future.

When planning consultation, the public service is expected to respect Māori and Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi interests. Departments are also expected to consider whether there are specific population and stakeholder groups that should be a particular focus of consultation given the Briefing subject matter.

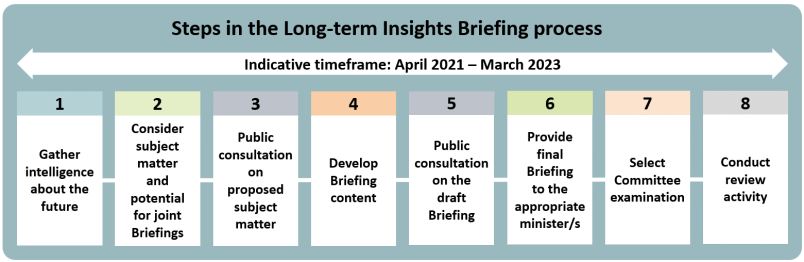

It’s expected departments will complete the first Briefings in time for ministers to present them to Parliament by 30 June 2022. The mid-election cycle timing maximises the Briefings’ potential to inform public and parliamentary debate, and political parties’ election manifestos before the next general election.

The Policy Project has developed guidance for departments on what to include in the Briefings and how to develop them. The eight-step process that departments are expected to follow is shown above.

The Policy Project was careful when developing the guidance to leave room for innovation and different operating contexts of departments. There’s a focus in the guidance on departments working together on joint Briefings to make connections between future trends that cross departmental functions.

There’s emphasis on the communication and engagement aspects of the Briefings which are as important as the research and analysis. Feedback loops from the first round of Briefings – at the department and public service level – will improve the next.

Once completed, the Long-term Insights Briefings will be a valuable resource for future policy development. Policy teams may wish to run sessions with their staff on what the long-term insights mean for their work and how they can be incorporated into future policy development.

How do you carve out space for the long term?#

What do you do to carve out space for the long-term in your policy practice? We invite you to share the tips and techniques you and your team use to provide policy advice that is fit for the future. Share your practical actions and reflections with #futurefitpolicy on Twitter or email the Policy Project.

We’d love to pull a list of ideas together that we can share with the policy community on how to carve out space for the long term.