The House Prices Unit conducted this study from August 2007 to December 2007, with the aim of reaching a better understanding of:

- The housing market as a national system. The relative importance and size of the influences of house price inflation. What it would take to slow house price inflation and potentially lessen the volatility of New Zealand's house price cycles or better manage their impacts.

- The consequences – for the macroeconomy, economic growth and social outcomes – of adjusting policy settings.

The Unit identified the impacts of house price increases across a variety of topics. This report summarises the findings of the Unit's analysis of the drivers of house price increases and their implications for economic and social outcomes.

Formats

1. Executive summary#

Housing affects a variety of social outcomes and is a critical component of household assets

Houses have a long life and vary greatly by type and location, and households typically make infrequent and long-lasting choices about housing. Housing provides a flow of services to households and is also an asset. As a flow of services, housing adds to individuals’ and families’ health, safety and well-being. Most of the benefits from housing services arise from the quality or the stability of housing arrangements, rather than from home ownership. Without stable, quality housing, households are at risk of poor outcomes.

Home ownership is important through housing’s role as an asset. Housing makes up just over 70% of household net wealth. As an asset, house prices can follow long, protracted cycles, with changes in prices affecting household wealth and decisions about spending and saving. Changes in house prices can contribute to wealth inequalities, with increases effectively providing a wealth transfer from non-home owners to home owners. The effect of these changes in asset values on household spending and saving decisions means that house price increases in the past five years have affected the macroeconomy, encouraging household spending, adding to inflationary pressures and pushing up interest rates and the exchange rate.

A surge in demand lifted prices, and while the number of dwellings has risen in line with the population, the cost of supplying new dwellings has increased sharply

Real house prices have increased by 80% since 2002.[1] Population growth, lower interest rates than during much of the 1980s and 1990s and increasing availability of credit have all boosted demand. Expectations of future price increases have also played a role, driving prices higher. The magnitude of this impact is highly uncertain. Meanwhile, the tax system has encouraged investors into housing, putting further pressure on prices.

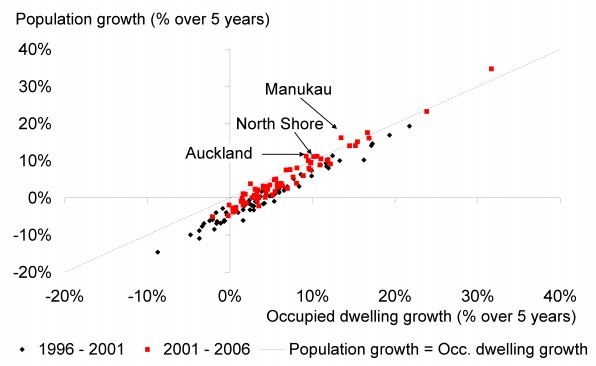

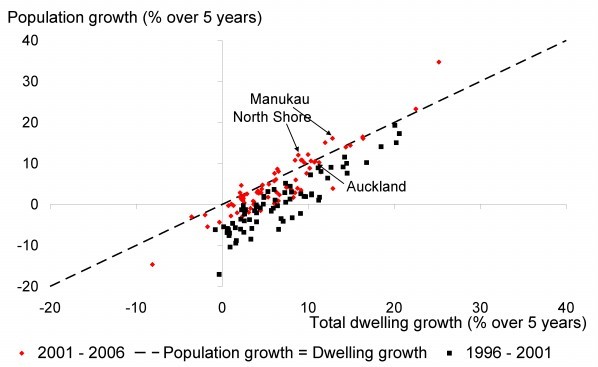

Supply responses in the housing market tend to be slow as it takes time to turn undeveloped land into new houses or to subdivide land. While the response was slow, the construction industry has responded to population growth, adding over 120,000 dwellings between 2001 and 2006 (with 110,000 new occupied dwellings). Not all regions have seen an increase in dwellings to match population growth, with shortfalls in supply emerging in some areas, particularly Manukau. In addition, demand has not been met in all segments of the market, particularly for lower income earners.

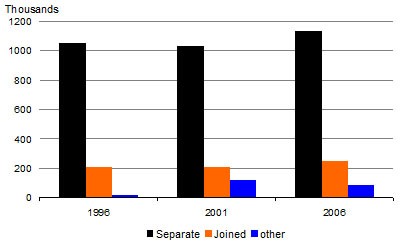

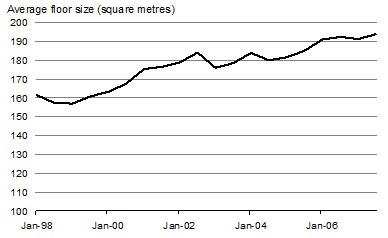

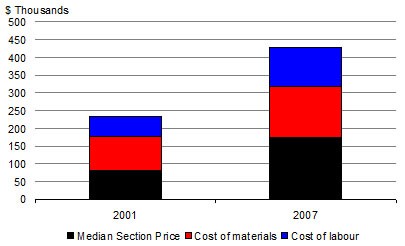

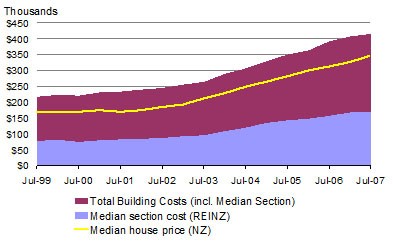

New supply has tended to come in the form of large, relatively expensive houses on the fringes of cities, which adds to pressure on infrastructure, or multi-unit dwellings, such as apartments. This surge in demand increased the construction industry’s need for resources and increased the prices of sections, materials and labour as well as lifting margins in the industry. The impact of regulations and council-imposed infrastructure levies has also added to costs.

The housing market is cooling, but prices are likely to remain high relative to incomes

House price growth has slowed and is likely to continue to ease over the next 12 to 18 months as interest rate increases begin to bite and expectations of future house price increases diminish. While expectations have been important, the judgment of the Unit is that longer-term structural factors have been the primary driver of high real prices. As a result, in the absence of an economic shock, adjustment to house prices is likely to be gradual, and it is possible that real prices could fall modestly in the next 1 to 2 years, rather than record a sharp fall.

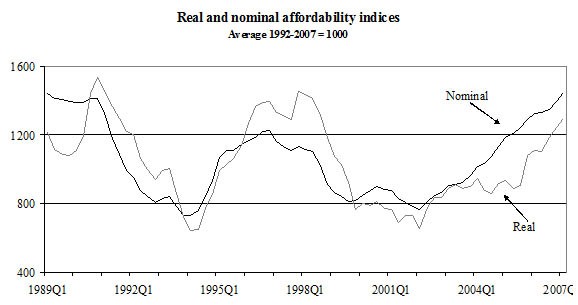

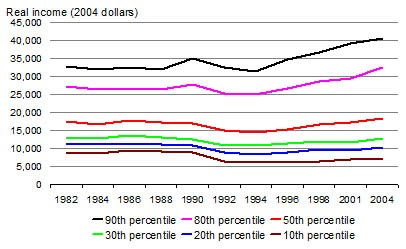

Rising prices have contributed to lower home ownership rates and constrained the housing market choices available to a growing group of New Zealanders

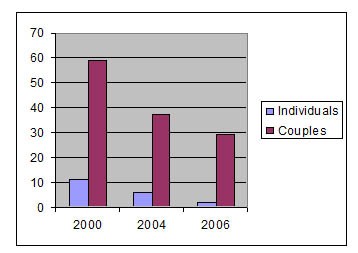

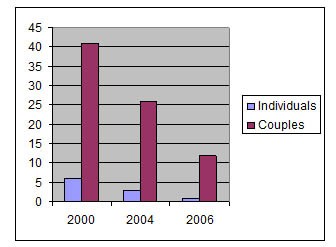

All measures of affordability have declined. By 2006, only 29% of renting couples and 2% of renting non-partnered individuals, with both groups including those people with and without children, could afford to buy a lower-quartile-price house in their region, and pay a maximum of 30% of their income in mortgage repayments. At current incomes and interest rates, even small falls in prices are unlikely to make a marked change in affordability. There is a growing group that cannot afford a mortgage on a house and is ineligible for state housing assistance that is likely to require secure long-term tenure arrangements in the private rental market.

Households require access to a wide range of choices, including the tenure and location of housing

As there is no single driver of house price inflation, mitigating the future effects of declining affordability will require a mix of new policy settings. The growing group that cannot afford home ownership needs access to a wider range of choices, including access to home ownership, longer-term rental arrangements to achieve security of tenure, a mix of providers of housing services and a wide range of choice of location of housing, particularly as fuel costs rise.

Reducing costs provides a sustainable way of making housing more affordable

Lower costs of sections and construction are the most likely way of achieving a long-term reduction in housing costs. A focus on streamlining regulatory systems, especially around the Resource Management Act and building consents processes, may help. Increasing the amount of land available for housing would also help, as would sustainable development, either in the form of intensive housing developments or new settlements built using sustainable methods and located outside of cities.

[1] The measure of real house prices used throughout this report is based on the nominal house price index compiled by Quotable Value New Zealand (QVNZ). The index has been deflated by the Consumers Price Index to calculate real house prices.

2. Introduction: house price increases and housing in New Zealand#

The House Prices Unit conducted this study from August 2007 to December 2007, with the aim of reaching a better understanding of:

- The housing market as a national system.

- The relative importance and size of the influences of house price inflation.

- What it would take to slow house price inflation and potentially lessen the volatility of New Zealand’s house price cycles or better manage their impacts.

- The consequences – for the macroeconomy, economic growth and social outcomes – of adjusting policy settings.

The Unit identified the impacts of house price increases across a variety of topics. This report summarises the findings of the Unit’s analysis of the drivers of house price increases and their implications for economic and social outcomes.

The following are the key features of the New Zealand housing market in recent years:

- Real house prices have increased by 80% since the beginning of 2002.[2] Real prices increased 67% between the 2001 and 2006 Censuses.

- At the aggregate level supply has responded strongly to population growth, and has exceeded population and household growth in many parts of the country, however, there are signs that shortages have emerged in Auckland.

- New supply has tended to be at relatively high prices meaning that new supply has not met the needs of all segments of the market, particularly people on lower incomes.

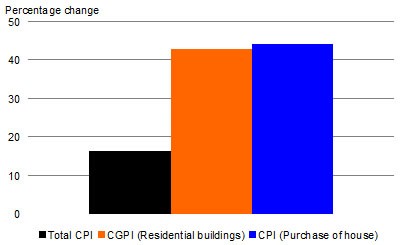

- The large increase in supply has come with higher costs. Land prices have increased sharply, while other costs related to constructing a dwelling, including materials and labour, have also recorded large increases.

- The price of rent has broadly moved in line with real income growth.

- Measures of home ownership affordability have declined during the boom in house prices.

- Prices are likely to remain relatively high in the foreseeable future, although some small falls in real house prices are likely as the market moves past its peak. These falls are unlikely to reverse the observed declines in affordability of the past four to five years at prevailing interest rates and income.

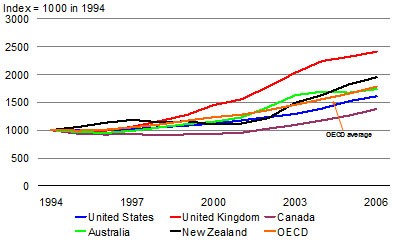

New Zealand’s recent boom in real house prices is unprecedented in comparison with historical trends, but it is not out of line with developments in many other OECD countries, including Australia and the United Kingdom. Unlike the United Kingdom, however, there are few signs in New Zealand of a shortage in the growth of dwellings relative to population growth during the boom in real house prices. The construction sector has responded to a large surge in demand driven by large net migration inflows, sustained real income growth, a period of low interest rates from 2001 to 2004 and an increase in the availability of credit; however, this response came with a large increase in costs. This cost increase reflects pressure on the price of sections, limits on the capacity of the construction sector, a large increase in demand for labour and skill shortages more widely across the economy.

The assessment of the Unit is that while some falls in real house prices are likely in the next two to three years as the housing market moves past its peak, the run-up in prices largely reflects developments in the New Zealand economy as well as the impact of the regulatory environment, and prices are likely to be maintained at relatively high levels. Nevertheless there are signs that housing market activity is slowing and it is possible that prices could fall modestly in the next 1 to 2 years. If consumer confidence is adversely affected by external and internal events, or if New Zealand experiences a significant weakening in growth as trading partner growth slows, then a more substantial easing in housing market activity and prices is possible.

Increases in house prices have raised the wealth of home owners and driven a widening gap between the affordability of houses and the incomes of people who aspire to own a home. Wealth inequalities within New Zealand have increased as a result.

The boom in house prices has had important implications for economic outcomes. It has encouraged household borrowing and spending and led to historically high levels of housing equity withdrawal, adding to inflationary pressures in the economy and contributing to an increase in interest rates and the exchange rate. The growing propensity of households to withdraw and spend some of their own rising equity also exacerbates cyclical upswings in the economy and makes management of the economy less predictable. At the same time, the location and type of housing have important implications for sustainability and New Zealand’s carbon emissions. Population growth and rising house prices can add to urban sprawl as households choose to move further out of core settlements to access relatively cheaper land. Section three of this report discusses the broad range of impacts associated with the boom in house prices.

Sections four to eight of the report provide a summary of the Unit’s analysis of housing market trends since 2001. Section four provides a statistical picture of the housing market, describes the existing government provision of housing-related assistance and describes the movements in New Zealand house prices. Section five provides a framework for analysing the factors affecting the demand and supply of housing, while sections six and seven provide a detailed analysis of these demand and supply factors. Section eight discusses the future outlook for prices.

Sections nine to thirteen discuss the impacts of the developments described in the previous sections. The analysis includes a discussion of the impacts on home ownership affordability and rent affordability as well as the economic and environmental dimensions of the housing market. Section thirteen proposes a direction for future policy based around improving housing market choices and reducing housing costs. Improving choices is about providing access to a wider variety of options for housing tenure and location. A focus on reducing costs is necessary to bring owning a home into the reach of a larger group of households.

The Unit has identified a number of areas where either the quality of available information makes it difficult, or the combination of issues means there has not been sufficient time, to reach strong conclusions. These are:

Information on the adequacy of land supply

- Scarcity of land that can be developed is one factor that appears to have contributed to higher section prices. While there are few signs of an absolute shortage of land for housing, there is little information available about how much land is ready, or close to being ready, for development.

Resource Management Act

- Developers argue that the land use decision process is lengthy, adds cost and limits their ability to provide an adequate volume of housing. Further research is needed to measure the costs to applicants of obtaining a resource consent.

Improving building productivity

- Preliminary work suggests that the New Zealand construction sector has exhibited low levels of productivity over the last 20 years. Increased gains from scale could be obtained if there was greater pre-fabrication and manufacturing of parts of the building. Further work is needed to understand how best to address these issues.

Infrastructure contributions

- There is variability between territorial authorities as to whether charges are applied and the size of the charges. This may be a reflection of different costs territorial authorities face in providing infrastructure, or the different funding choices territorial authorities are making. It could also be an indication of inconsistency and variable interpretation of the power to levy found in the Local Government Act. Further work is needed to understand the impact that the variability and levels of infrastructure contributions have on the cost of new housing.

[2] Note that the term ‘house prices’ is used throughout this report to cover the prices of all types of dwellings.

3. Why housing and house prices matter#

- Home ownership is closely linked to asset accumulation, especially during a period of rising prices. Rising house prices have added to wealth inequalities.

- Economic performance is affected by house price changes. Volatile house prices make monetary policy more complicated, and there are potential spillovers to the tradables sector.

- Quality of housing is important for health outcomes.

- Location and design of cities affects carbon emissions.

What housing is

Housing has multiple attributes. Homes provide shelter and space for family living; they also provide a location within a neighbourhood that influences access to an array of private services and public activities that households regularly use, such as work, schools, shopping centres and leisure facilities. There is a plethora of studies that show how all these attributes of houses influence the value of homes, and the ways in which people use them. And, of course, for the majority of households in New Zealand, purchasing a home also provides an asset. As a result of all these interactions, housing touches on a range of outcomes. Its status as a durable asset means that housing also has strong links to financial markets and the construction sector, with dwelling construction peaking at 6% of GDP from 2003 to 2005.

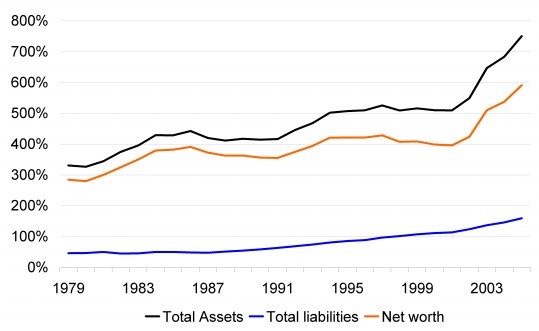

The housing market is an important element of the macro-economy. Housing accounts for 22% of average household expenditure for owner-occupied households and 28% of renting households’ average household expenditure (Statistics New Zealand, 2007).[3] Housing also makes up a substantial portion of household assets, with Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) data showing that housing’s share of total household net wealth has increased from around 60% in 1978 to just over 70% by 2006. The surge in housing as a share of net wealth reflects sharp house price increases since 2002. As an asset, houses can be bought and sold at a profit or a loss, and prices can follow long, protracted cycles, with changes in prices affecting household wealth and decisions about spending and saving.

Making connections

As a flow of services, housing adds to individuals’ and families’ health, safety and well being. Good housing can create positive spillovers for households, and poor housing the converse. The importance of the services that housing provides can be separated into those areas that are related to good quality housing, stable housing, neighbourhood effects and home ownership. In recent years there have been a number of country-specific attempts to review the value of benefits from good housing and the type of tenure, not least insofar as they impact on the wellbeing of children and educational outcomes as well as health effects. In the New Zealand context strong evidence has only been gathered in the health sector.

Importance for health outcomes

There are a number of New Zealand studies that demonstrate a link between the quality of housing and health outcomes. This link is not about the type of tenure but about the quality of housing. Quality, in turn, is related to income, with higher income earners generally able to attain high-quality housing.

Maani, Vaithianathan and Wolfe (2006), show a link between health outcomes and the quality of housing, with people living in crowded dwellings achieving substantially poorer health outcomes. Maani et al. suggest that income is the key driver of crowding and therefore poorer health outcomes. Baker et al. (2006) also suggest that overcrowding is associated with elevated rates of hospital admissions for both communicable and non-communicable diseases, while Saville-Smith and Amey (1999) show that overcrowding is an important factor in health outcomes in rural locations as well as in towns.

Research from the Wellington School of Medicine and Health Sciences demonstrates that when homes are properly insulated there are significant health gains (Howden-Chapman et al., 2007). The study found insulation resulted in:

- A 30% reduction in the frequency with which occupants were exposed to temperatures below 10°C.

- A 3.8% fall in mean relative humidity causing dampness.

- Decreased energy consumption, with insulated houses using 81% of the energy of non-insulated houses. This may also result in greater disposable income, which can be spent on food and clothes.

These results show significant improvements (10%–11%) in the health and quality of life of the occupants due to insulation. The research also found that:

- Adults and children occupying well insulated homes have reduced wheezing, colds and respiratory problems (40%–50% reduction).

- People living in insulated houses are less likely to take days off work and school (40 - 50% reduction) than people in houses without insulation.

- People living in insulated homes had fewer visits to general practitioners and fewer hospital admissions for respiratory conditions.

- People living in warm houses were less likely to shift houses, which the research suggested had positive benefits for children's education.

Further information about the heating of houses is available from the Household EnergyEnd-use Project (HEEP) (Isaacs et al., 2006). The HEEP data shows that while low income households appear to value increased warmth they are unable to achieve warm indoor temperatures, despite spending a higher proportion of their income on energy. This is likely to put lower income households at risk of poor health outcomes. Nearly 50% of Maori households in the HEEP survey had mean winter evening living room temperatures categorised as ‘cold or below average’, compared with 40% of all surveyed households.

Importance for other social outcomes

New Zealand evidence regarding the social and educational implications of housing is sparse. Internationally, a number of authors have suggested a link. Barker (2004) cites United Kingdom research showing that poor housing, particularly temporary housing, affects the educational achievement of children.[4] It is not clear whether this benefit is directly related to the stability of tenure or whether income or some unobserved variables are the important factors. DiPasquale and Glaeser (1999), draw a direct link between home ownership and greater civic effort, and Rohe et al. (2001) have pointed to positive relationships between home ownership and satisfaction with homes and neighbourhoods.

New Zealand evidence on these influences is limited. Motu is carrying out research in the next two to three years that will help address the extent to which home ownership is associated with positive economic and social outcomes, compared with importance of the quality of housing and the stability of tenure.

Home ownership: benefits and aspirations

In New Zealand during the past 50 to 60 years, home ownership has been the main route to attain the benefits of quality housing and the stability of tenure discussed above, for those people with the income to sustain it. New Zealand evidence on the direct relevance of home ownership is limited, although it is likely that most benefits from housing services arise from the quality and/or the stability of housing arrangements, rather than home ownership itself.

Owning a home is an important aspiration for New Zealanders. Focus group research with renters indicated that participants aspired to being an owner-occupier within 10 years (DTZ, 2005). Focus-group research points to home ownership being valued for a number of different reasons:

- Ability to personalise the property.

- Investment and wealth dimensions.

- Security and social status benefits.

There is a growing group of renters, at all but the highest levels of income, whose home ownership aspirations will not be met given current prices, interest rates and levels of income.

Importance for standard of living in retirement

Analysis by the Ministry of Social Development (MSD) (2006) of living standards in New Zealand found that, in 2004, older people who owned their own home had the highest average living standards amongst older people, and were less likely to be in hardship than those who rented. In the study, 58% of people aged 65 or older who owned their own home were recorded as having a good standard of living, with 37% having a comfortable living standard. The equivalent numbers for private renters were 19% and 57% respectively, with 13% and 46% for Housing New Zealand Corporation (HNZC) tenants.

MSD notes that the housing costs of older home owners who have paid off their mortgage are minimised, resulting in a higher standard of living. While this will be true in many cases it is possible that a household that always rents, and saves the money they would otherwise have paid as mortgage payments, could be no worse off when they retire than someone who owns their home, depending on the returns to housing compared with other assets.

Those older people with housing costs of over $200 a week tend to have lower average living standards than those with lower housing costs, reflecting the fact that those with higher living costs are more likely to be paying rent or mortgages on capped incomes. This result is also likely to be related to the previous income levels of retired people, with higher-income people more likely to have been able to pay off a mortgage during their working life and, therefore, able to enjoy lower housing costs when retired.

Importance for asset accumulation and wealth inequalities

Rising house prices have increased the net wealth of home owners and can contribute to net wealth inequalities. Net wealth per capita doubled between 1980 and 2001 and doubled again from 2001 to 2006 as a result of the house price boom. The increase in net wealth arising from increases in other assets was substantially smaller.[5]

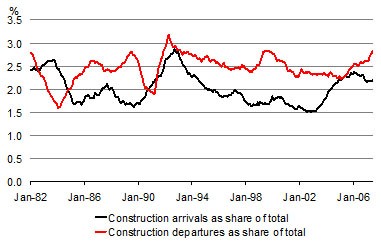

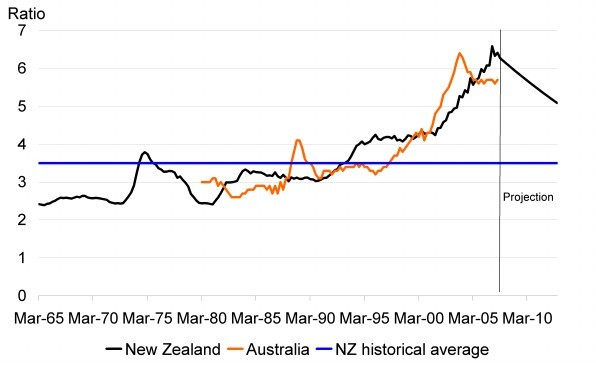

Figure 1: Net worth as a percentage of household disposable income

|

|

Source: RBNZ |

International research suggests that holding household assets can provide home owners with a greater sense of opportunity and security (Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion cited in HM Treasury, 2005). Property can be used as collateral to secure loans. Owning a house can also provide security against future rises in housing costs, and it provides rent-free accommodation in retirement (HM Treasury, 2005). Home ownership can also have inter-generational effects through wealth transfers and inheritances, which often provide additional funds to households and individuals in middle life with middle to higher incomes (Thorn, 1994).

Housing assets are not distributed equally. When prices increase there is a redistribution of wealth from non-home owners to existing home owners. Non-home owners have to save a larger deposit to buy a house, or take on more debt. Existing home owners can use the increased equity to borrow against for consumption, or accumulate more assets, or they can sell their house and capture the equity increase.[6] These wealth inequalities can be transferred over time through wealth transfers among home-owning families.

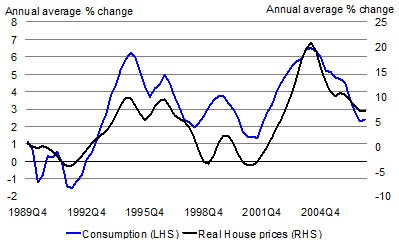

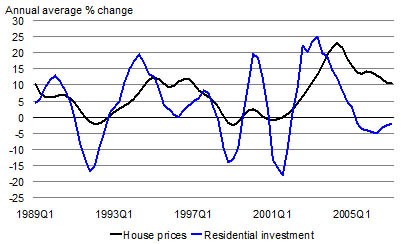

Importance for economic performance

There are a variety of interactions between changes in interest rates, house prices and domestic demand. Lower interest rates from around 2001 to 2004, compared with New Zealand’s historical experience, contributed to a lift in house prices. In turn, these high house prices encouraged household spending and lifted inflationary pressures, eventually leading to higher interest rates and contributing to a higher exchange rate. These developments have reduced the returns received by exporters but effectively boosted the real disposable income of consumers who purchase imported goods.

In the Supplementary Stabilisation Instruments report (Reserve Bank of New Zealand and The Treasury) prepared in 2006, the RBNZ and The Treasury conclude that house price increases and expectations of future increases have seen asset values increase sharply and private consumption rise. Home owners have felt wealthier and have therefore spent more. The increase in house prices has effectively eased credit constraints and many households have accessed the higher level of wealth by increasing mortgages on their properties.

In her review of housing supply in the United Kingdom, Barker (2004) notes that instability in the housing market can be associated with volatility in economic activity, owing to the link between house prices, credit constraints and household consumption. This means that volatility in the housing market can be transmitted into volatility in the rest of the economy, which may not be able to be fully offset by policy. Barker suggests that macroeconomic instability can have a damaging effect on the level of business investment and long-term growth prospects.

Oswald (cited in Cochrane and Poot, 2007) suggests that home ownership is detrimental to labour market flexibility because the transaction costs involved in shifting dwelling discourage people from moving to take up employment opportunities elsewhere. New Zealand evidence is mixed. Mare and Timmins (2004, cited in Cochrane and Poot, 2007) find that responsiveness to relative employment performance is greater when home ownership is higher, contradicting the results of Oswald. In their own analysis, Cochrane and Poot find a statistical relationship between home ownership and unemployment rates, but do not establish whether there is a causal relationship or whether it is spurious.

An additional link from housing to economic performance could arise through the effect of high housing costs on internal and external migration decisions. People may be reluctant to move internally within New Zealand to regions with high house prices, which would affect firms’ ability to acquire labour in some regions of New Zealand. Motu (2006) suggest that there is evidence of this occurring in the Nelson, Tasman and Marlborough areas, where firms have had difficultly retaining and attracting key workers. Affected industries include resource based industries, such as fishing, farming and horticulture, as well as tourism, education and health. High house prices may also discourage skilled migrants from coming to New Zealand. Department of Labour studies suggest that the quality and price of housing is a key disappointment for migrants after arriving in New Zealand (Department of Labour, 2005). There is no evidence available as to whether it is an important factor influencing migration decisions.

Importance for New Zealand’s carbon emissions and the sustainability of cities

Housing market outcomes have implications for sustainability. Urban design and the location and type of housing influence New Zealand’s carbon emissions and the sustainability of New Zealand’s cities. Population growth has the effect of increasing the size of cities and is contributing to growth in carbon emissions. To mitigate these impacts, housing policy needs to be well integrated with the provision of efficient public transport systems.

Higher land prices also encourage more intensive forms of housing. This can be an effective way to accommodate a growing population. Nonetheless, intensive forms of housing are also associated with a requirement for new infrastructure. For example, without investment in public transport, traffic congestion would increase.

The rising costs of fuel and peoples’ desire to avoid traffic congestion suggests that there will be increased future demand for housing that is close to employment and leisure activities and well serviced by public transport. All future development will need to minimise the environmental impacts of population growth.

Summary

The broad range of impacts from housing means that housing outcomes have direct implications for the following priority areas of Government:

- National identity: through the role of aspirations for home ownership.

- Families young and old: as a result of asset accumulation, wealth inequalities and health and social outcomes.

- Economic transformation: through the impacts on household behaviour when house prices change.

- Sustainability: as a result of the location and type of housing.

[3] Statistics from Household Economic Survey.

[4] Department of Education and Science, 1990, cited in Barker, 2004.

[5] Estimates derived from Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) household wealth data.

[6] Owning a home can be seen as a hedge against rising housing costs. When house prices increase, the future housing costs of a household increase. A home owner has a natural hedge against this as they own the house.

4. Background statistics#

4.1 The New Zealand housing stock#

The 2006 Census recorded a total of 1,651,542 dwellings in New Zealand, with 1,478,709 classified as occupied dwellings and 172,836 unoccupied dwellings. The majority of the occupied dwellings are classified as private, in that the dwelling is not usually available for public use. In the 2006 Census there were around 7,000 occupied non-private dwellings, with hotels/motels accounting for around half of the non-private occupied dwellings and institutions such as hospitals and prisons accounting for just under a quarter of non-private occupied dwellings. Empty dwellings accounted for almost two thirds of the total number of unoccupied dwellings.

Table 1: Dwelling occupancy status 2006 Census

| Number of dwellings | |

|---|---|

| A Occupied dwelling | |

| B Occupied private dwelling with resident(s) | 1,454,175 |

| Occupied private dwelling with no usual resident(s) | 17,751 |

| Total occupied private dwelling | 1,471,749 |

| C Occupied non-private dwelling | 6,693 |

| Total Occupied dwellings | 1,478,709 |

| D Unoccupied dwelling | |

| E Residents away | 49,122 |

| F Empty dwelling | 110,154 |

| G Dwelling under construction | 13,560 |

| Total | 1,651,542 |

Notes

A A dwelling is any building or structure, or part thereof, that is used (or intended to be used) for the purpose of human habitation. An occupied dwelling is occupied at midnight on the night of the census or at any time during the 12 hours following midnight on the night of the census.

B Private dwellings are not usually available for public use.

C Non-private dwellings are available for public use and include hotels and motels, prisons, hospitals, boarding houses, residential care facilities.

D Unoccupied at all times during the 12 hours following midnight on the night of the census, and suitable for habitation.

E Where occupants of a dwelling are known to be temporarily away and are not expected to return by noon on the day after the data collection.

F Where a dwelling clearly has no current occupants and new occupants are not expected to move in on or before the date of the date collection. Unoccupied dwellings being repaired or renovated are defined as empty dwellings. Unoccupied baches or holiday homes are also defined as empty dwellings.

G All houses, flats, groups or blocks of flats being built.

4.2 A snapshot of housing tenure#

Table 2, below, shows how the home ownership rate has changed during the past 25 years and table 3 provides the sector of landlord for non-owner-occupied dwellings. In the 2006 Census, those households living in a house owned by a trust in which they are a member are classified as living in an owner-occupied house. Prior to the 2006 Census, some households in this living arrangement were not captured as owner-occupiers. The Briggs adjusted series in table 2 adjusts the pre-2006 Census home ownership rates to more adequately capture those households living in homes owned by a trust in which they are members, by classifying them as home owners. Around 50% of owner-occupiers make mortgage payments.

Table 2: Home ownership rates

|

|

1981 |

1986 |

1991 |

1996 |

2001 |

2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

New Zealand (% of homes owner-occupied) |

71.4 |

73.7 |

73.8 |

70.7 |

67.8 |

66.9 |

|

Briggs adjusted for trusts |

74.9 |

72.3 |

70.5 |

66.9 |

Table 3: Sector of Landlord

|

|

1996 |

2001 |

2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Private Person, trust or business |

196,188 |

264,501 |

299,607 |

|

Local Authority or City Council |

14,781 |

14,118 |

11,004 |

|

Housing New Zealand Corporation |

52,688 |

52,500 |

49,419 |

|

Other state owned enterprise or government department |

8,370 |

6,432 |

6,165 |

Sources: Statistics NZ, DTZ

The Census data provided in table 3 is an undercount of the actual number of Housing New Zealand Corporation (HNZC) dwellings. HNZC owns around 67,000 dwellings, with the Census consistently under-reporting the actual number of HNZC dwellings.

Characteristics of landlords

Rising house prices have attracted investors into the housing market. In an analysis of Survey of Family Income and Employment (SOFIE) data, Scobie, Gibson and Le (2007) found that 15% of all households in New Zealand owned an investment property, including holiday homes, rental property, timeshares and overseas property. Scobie et al. found that around 12% of households in the 45-54 age groups owning investment properties, compared with 5% in the 25-34 and 65-74 age groups. Of those households that owned investment property, Scobie et al found around 50% owned two investment properties and around a third own one property. The ANZ Property Investors Survey (ANZ, 2007) shows that property investors tend to be higher income earners, with mean annual household income of property investors of $80,000-$90,000, with 37% having household income in excess of $100,000.

The National Landlord Survey (Centre for Research, Evaluation and Social Assessment, 2003) identified the following benefits as being identified by landlords:

- 38% cited the benefits of capital gain

- 32% cited regular income stream as a benefit

- 25% cited retirement investment/income as a benefit

- 9% cited tax advantages as a benefit

- 8% cited rent paying off the mortgage as a benefit of owning rental property.

The National Landlord Survey also found that over 20% of landlords had been landlords for less than a year and over 50% had been landlords for less than eight years.

4.3 Forms of government intervention in the housing market#

A number of government interventions either directly or indirectly provide financial support to home-owners, renters and providers of private rental housing. The total value of government interventions that relate to housing is around $7.5 billion p.a.

The tax system

- implicit assistance for existing home owners through the non-taxation of imputed rents (around $4.2 billion p.a.) and non-taxation of capital gains (around $3.1 billion p.a.). In aggregate, the former is offset by not allowing mortgage interest deductions (equivalent to around $4.2 billion p.a.) although the impact on individual owner-occupiers depends on how much equity they have in their property.

- implicit assistance for providers of rental housing through the non-taxation of capital gains (around $1.1 billion p.a.) and by allowing the deductibility of rental losses against other income (around $1.1 billion p.a.).

Section 6.8 contains a more detailed discussion of the impact of the tax system on housing.

The benefit system

The Accommodation Supplement (AS) is a non-taxable benefit that provides assistance towards accommodation costs. A person does not have to be receiving a benefit to qualify for the AS. The AS can be used to pay the cost of rent or to make mortgage payments. In the year to June 2007, $877 million was paid to 250,000 people through the AS, up from $830 million in 2006.

The nominal total cost of the AS increased from $711 million in the June 2002 year to $877 million in the year to June 2007. Over the 2002 to 2007 period, the number of recipients fell from 258,000 to 250,000, with average payments increasing as housing costs increased and with more people receiving the maximum payment. The number of people receiving the maximum AS payment has increased from just over 40,000 people (around 16% of recipients) in 2002 to over 60,000 people (or 26% of recipients) in 2007. Around 80% of people receiving the maximum payment were renters.

Social housing assistance

Provision of social housing is made through Income Related Rents funding to HNZC ($436 million in the year to June 2007) for 59,000 households and for housing at market rates for around 8,000 people.

Other small-scale programmes

Small-scale policy interventions to support households into home ownership are currently provided through programmes such as:

- Welcome Home Loans (3,000 people since September 2003)

- Shared equity pilot scheme beginning in July 2008

- KiwiSaver (projected to assist 1,400 people into home ownership each year from 2010)

- The Housing Innovation Fund (HIF) provides support for the non-government social housing sector, including capital grants, interest rate subsidies and capacity grants ($12 million in capital funding and $3.7 million in operating funding in the year to June 2008, with assistance provided to 72 projects since 2003).

Additional supply of 1000 affordable houses per annum is possible as a result of the proposed Affordable Housing: Enabling Territorial Authorities Bill.

4.4 Real house prices have increased 80% and have lifted across all of New Zealand#

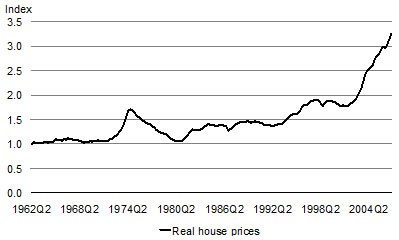

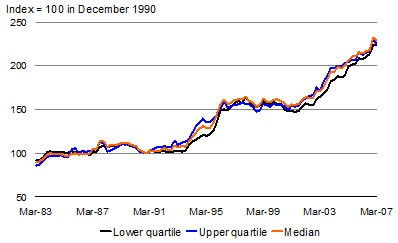

The boom in real house prices that began in 2002 is unprecedented in New Zealand’s recent history. Real house prices increased by close to 80% between March 2002 and March 2007, around the same increase as was recorded across the entire 1962–2002 period (see figure 2). While unprecedented in New Zealand’s experience, such an increase has been a feature of many developed economies over the past 10 years (figure 3).

Figure 2: Real house prices

|

|

Source: QVNZ, Statistics New Zealand |

Figure 3: OECD real house prices

|

|

Source: OECD[7] |

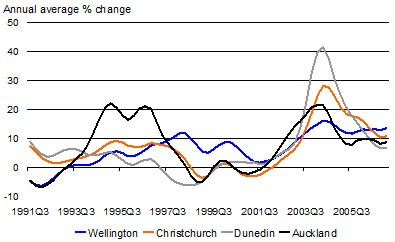

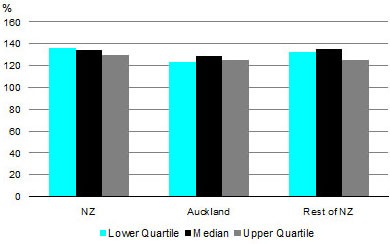

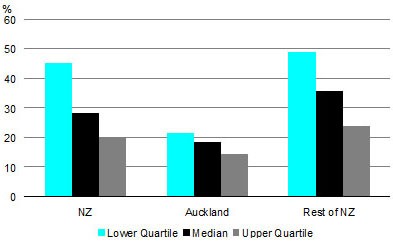

The boom in real house prices has occurred across all regions of New Zealand. This differs from the mid-1990s boom which was largely based in Auckland. The lift in prices since 2002 has affected all classes of dwellings, whether they are at the top end of the market or more modestly priced. Real prices increased first in Auckland. The rate of growth in other cities, where the level of prices is lower, did not begin to accelerate until 2003. While the percentage changes in real prices have been largest in Christchurch and Dunedin, where the price level is lower, the biggest increase in dollar terms has come in Auckland. The top end of the market, represented by the upper quartile real house price, increased first, edging up in 2002, while the lower end of the market remained relatively flat. This is illustrated by real price movements in Auckland in figure 5. Once prices in the lower end of the market did begin to rise they lifted sharply, with the lower quartile price generally increasing at a faster rate than the median and the upper quartile from 2003 to 2007.

Figure 4: Regional real house price changes

|

|

Source: QVNZ, Statistics New Zealand |

Figure 5: Auckland real house prices by quartile

|

|

Source: QVNZ, Statistics New Zealand |

Figure 6: Real price changes March 1990-March 2007

|

|

Source: QVNZ, Statistics New Zealand |

Figure 7: Real price changes March 2004-March 2007

|

|

Source: QVNZ, Statistics New Zealand |

The increases in house prices have generally been exceeded by increases in section prices, particularly during a period from the middle of 2003 until late in 2005, where section prices accelerated sharply. Grimes and Aitken (2006) attribute almost all of the increase in house prices between 1981 and 2004 to section prices. Section 7 contains a discussion of movements in land prices.

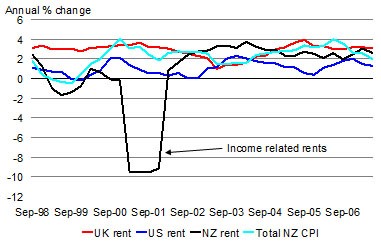

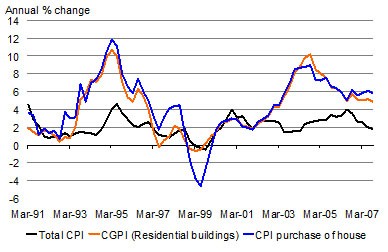

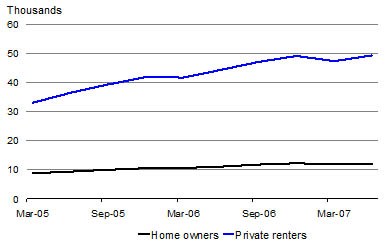

One feature of the boom in house prices is that it has not been associated with sharp increases in rent, in part due to the large increase in the availability of rental properties; there have been smaller increases in rents than have been recorded in the United Kingdom. This may reflect a smaller increase in the occupied dwelling stock relative to population growth in the United Kingdom. The Consumers Price Index (CPI) is the official measure of changes in rent, and tries to control for changes in the composition and quality of rental accommodation.

Figure 8: Rent price component of CPI

|

|

Sources: Statistics New Zealand, Datastream |

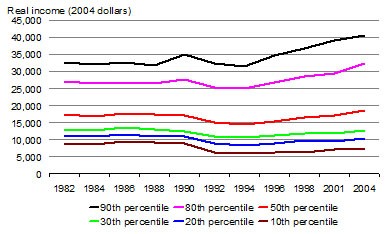

Figure 9: Real income by percentile

|

|

Source: Ministry of Social Development |

4.5 Real income growth has been uneven across the income distribution#

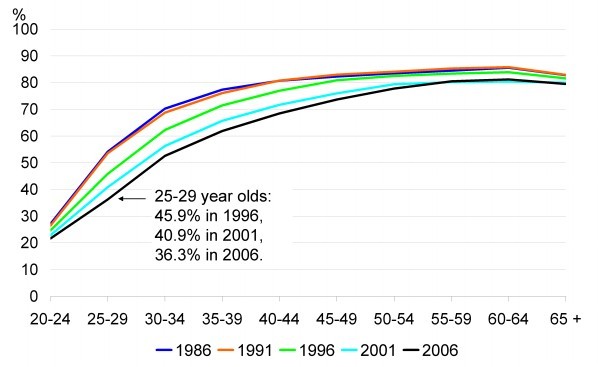

- Between 1982 and 2004, real household income gains were concentrated at the higher parts of the income distribution.

- Between 1982 and 2004, real incomes increased close to 25% for the 90th percentile of earners (the highest 10% of earners), while at the 50th percentile (median income level) real incomes increased around 6%.

- Real household incomes fell for the lowest 30% of income earners, with the falls coming in the 1982–1996 period. From 1996 to 2004 there were small increases in real household incomes for the lowest 30% of income earners (Perry, 2007).

Comparable data is not available for the period from 2004 to 2007. New Zealand Income Survey data shows that from 2004 to 2007 the upper band of the level of real income of the lowest 20% of income earners (individuals rather than households) has increased by 9.2% (or $15 a week in 2007 dollars), while the lower band of the income of the highest 20% of earners has increased 11% (or $80 a week). The introduction of the Working for Families package has contributed to the increases at the lower part of the income distribution since 2004.

[7] The OCED average is not weighted for the size of the housing stock in each country and does not include prices in Turkey, Luxemburg, Mexico, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Hungary, Greece and Iceland.

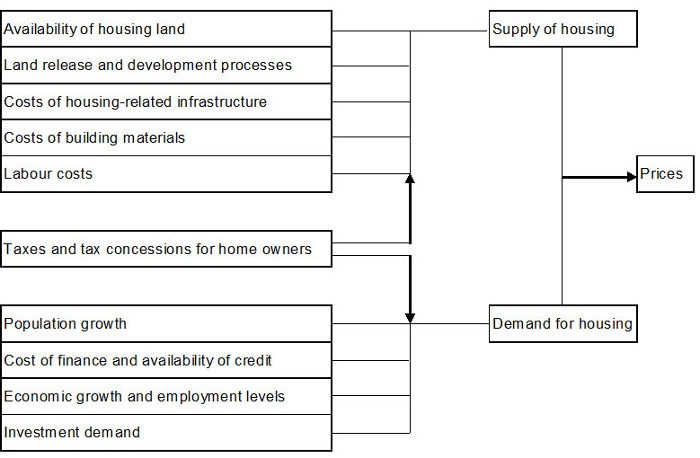

5. Framework for analysing house price increases#

No one factor can account for the increase in house prices since 2001. The trends in house prices are the net outcome of all the factors that affect supply and demand.

Source: Adapted from Australian Productivity Commission: First Home Ownership.

Some demand and supply factors are cyclical in nature and short-lived while others are structural and influence prices over the medium to long term. The factors affecting demand are discussed in section 6, the factors affecting supply are discussed in section 7. Prices are one of the determinants of the affordability of housing, with the cost of finance, taxes and income levels, being other key determinants.

In the short term, generally less than a year in New Zealand, the supply of housing is relatively fixed, or inelastic, so that increases in demand push up prices. In the longer term, the supply of housing is more elastic as developers respond to new demand and rising prices. In general, the long-term supply curve is less than fully elastic so that as housing demand rises, supply of new units will rise but so will prices. Ways of avoiding price increases with rising long-term demand include new technologies that reduce building costs, or some other favourable shift in the supply of the factors involved in building homes; for instance a pervasive reduction in the price of land, that shifts the supply curve out. Price increases can be avoided if the unit costs of building a dwelling remain constant, as in the case of a completely elastic supply curve. Reducing demand, for example through the tax system, could also reduce pressure on prices.

6. Demand factors#

- Large increases in the size of the population, growth in the number of households, growth in real incomes, a period of low interest rates and increasing availability of credit have all contributed to rising demand for housing.

- Rising investor interest and expectations of capital gains have also played a part.

- Future demand will be underpinned by population growth and demographic changes, such as population aging, meaning that demand for housing is likely to grow at a faster rate than population growth.

6.1 Household formation trends#

Household formation has increased at a faster rate than population growth, owing to changes in household size and composition. Between 2001 and 2006, the number of households in New Zealand increased 8.2%, compared with population growth of 7.7% and a 6.0% increase in the number of households between 1996 and 2001. Between 1986 and 2006, the proportion of households made up of couples with children has declined from around 37% of households to 27%. The share of one-person households has increased from 19% in 1986 to 22% in 2006. The share of couple-only households has also increased.

These recent trends are projected to continue in the future and the number of households, and therefore the number of houses needed for them to live in, is projected to continue to increase at a faster rate than the projected increase in population. Average household size is projected to decline from 2.7 people per dwelling in 2006 to 2.4 in 2021 (Statistics New Zealand, 2005). This is due to a projected increase in the older-age population and a decrease in the average size of family households as women have fewer children.

Impact on demand

Projected household and population growth suggests that New Zealand will need an additional 200,000 dwellings between 2006 and 2016.[8] This is in addition to any extra demand for holiday homes or other forms of second homes that are not available for permanent accommodation. Future growth in dwellings will therefore need to be around 20,000 per year to accommodate expected demand, plus any additional demand for second homes. This will underpin ongoing demand for housing. This rate of increase is only a little under the average growth achieved during a construction boom from 2001 to 2006, which averaged around an additional 22,000 occupied dwellings and 25,000 total dwellings per year, with the difference accounted for by unoccupied dwellings, including holiday homes. Generating this additional supply may pose some difficulties if some of the conditions that have boosted supply in recent years do not exist in the future, including the strong demand from investors and relatively low interest rates.

6.2 Population and migration#

Changes in the size of the population and household numbers are important drivers of the demand for dwellings. Population growth occurs through natural changes in the population from births and deaths and through patterns of inward and outward migration. Between 2001 and 2006 the New Zealand population increased by 7.8%, well above the rate of population growth of 3.2% between 1996 and 2001.[9] Growth in Auckland accounted for 47% of the population growth of New Zealand as a whole. While the population of Auckland increased between 2001 and 2006, around 76,000 people moved out of Auckland to another region of New Zealand over the same period, and around 59,000 moved into Auckland from another New Zealand region, illustrating a net loss of population from internal migration.

Future population growth is not projected to be consistently as fast as during the period from 2001 to 2006, however, population growth is forecast to continue, with the population size expected to reach five million within the next 20 years, underpinning demand for housing in the future. In addition, major population surges, due to immigration and/or emigration, may reoccur in response to domestic and international developments.

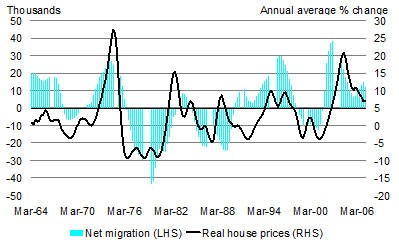

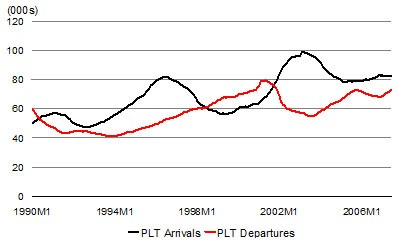

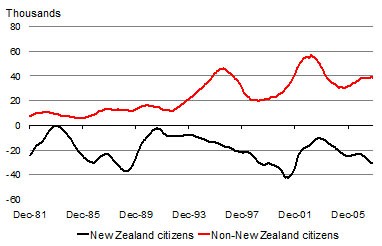

Since the 1960s New Zealand has experienced a number of periods of sizable upswings and downswings in net migration. The numbers and ages of people entering and leaving New Zealand have important implications for the demand for housing. The sharp increase in permanent and long-term arrivals from late 2001 was driven by people aged 15–24 and 25–39. The 15–24 age group saw a particularly large increase, in part due to a surge in the number of students coming to New Zealand. The annual net arrivals of New Zealanders briefly increased from 20,000 to 25,000 following the terrorist attacks in the United States of September 2001.

Temporary arrivals of longer than one year are an increasingly significant feature of migration in New Zealand, with 87% of principal applicants approved for residence in 2005/06 previously holding a temporary visitor, student or work permit. Around 30% of temporary migrants became permanent residents over the same period. As a result, it is the temporary inflows that are the major driver of arrivals, not permanent residency approvals. Temporary inflows are largely demand driven, provided an applicant meets the relevant criteria. There is no cap on temporary arrivals, whereas permanent residency approvals are capped (currently set at 45,000–50,000 per year). In addition, returning New Zealanders are a major source of migration volatility. This is a demand-driven response that is not open to regulation.

Departures from New Zealand fell from around 80,000 in 2001 to 60,000 in 2003, further adding to the net migration inflow. The sharpest falls in departures were in the 25–39 age group, where departures fell by around one third. This is an important age group for household formation and demand for housing, so the decline in departures would have added to housing demand.

Figure 10: Annual migration and house prices

|

|

Sources: Statistics New Zealand, QVNZ |

Figure 11: Annual departures and arrivals

|

|

Source: Statistics New Zealand |

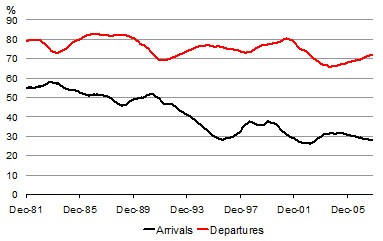

Figure 12: Share of annual PLT arrivals and departures that are New Zealand citizens

|

|

Source: Statistics New Zealand |

Figure 13: Annual net migration flows

|

|

Source: Statistics New Zealand |

Impact on demand

Around 120,000 people were added to the population from net migration between June 2001 and June 2007 (equivalent to around 3% of the population), increasing the demand for housing at a much faster rate than supply could easily respond to.

International studies suggest that the impact of population growth on house prices is relatively small, with a 1% increase in the population associated with a 1% increase in house prices (Saiz 2003, cited in Coleman and Landon-Lane 2007). Direct New Zealand evidence is limited; however, a recent paper by Coleman and Landon-Lane suggests that a net migration inflow of 1% of the population is associated with an 8%–12% increase in house prices after one year, and a slightly larger effect after three years. The authors note that the size of this impact seems implausible and suggest three possible explanations why it lasts for such a long period, even after supply has responded:

- If the construction sector is capacity constrained, house prices and construction costs would be high until the stock of housing caught up with increased demand.

- Migration flows could be correlated with other factors that are boosting house prices, for example, future income expectations.

- Migration could destabilise expectations about house prices.

The source of migration trends has important implications for the housing market. A new study on migration and house prices is currently underway, being conducted for the Department of Labour by economists at Motu. Preliminary results for 1986 to 2001 indicate that there is a relationship between the population in an area and the level of house prices; similarly there is a relationship between the change in the population and the change in house prices. The results suggest there is a relatively small effect on the prices of houses or rents from new immigrants to New Zealand. In contrast, there appears to be a significant relationship between returning New Zealanders and the changes in local house prices from 1986 to 2001. Non-New Zealand born migrants may have different patterns of housing tenure to other residents, temporary migrants in particular are more likely to rent if they do not expect to stay long in New Zealand.

Care is needed in interpreting these results as they do not establish a direction of causality. On the one hand, it could be that returning New Zealanders do add pressure on houses prices. Equally, it could be that New Zealand born individuals repatriate at the time there is strong economic growth and an active labour market. These factors may in themselves lead to upward pressure on prices rather than the flow of migrants per se. Migration might merely follow job growth and rising house prices rather than be an underlying cause of rising house prices.

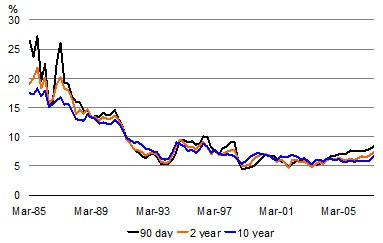

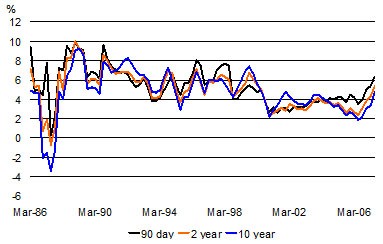

6.3 Interest rates, inflation, financial deregulation and the availability of credit#

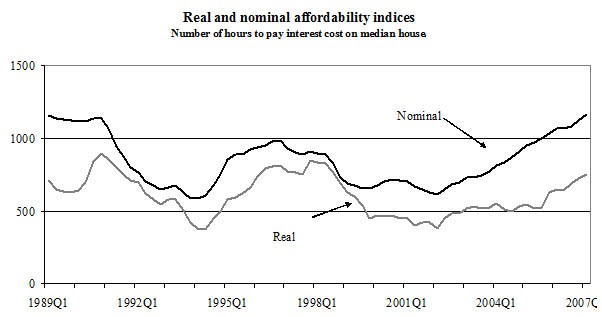

Nominal and real interest rates have moved down sharply over the past 20 years. From 1985 to 1990, nominal 90-day interest rates fluctuated between 15% and 25%. A low inflation environment following the introduction of the Reserve Bank Act in 1989 saw nominal interest rates gradually trend down. A slowdown in world economic growth around 2000/01, together with expectations of weak growth following the terrorist attacks in the United States, saw expectations of growth in New Zealand downgraded. The RBNZ cut the Official Cash Rate (OCR) to 4.75% by the end of 2001.

During this period, central banks around the world also cut interest rates, which, in combination with large amounts of liquidity resulting from current account surpluses in Asia, saw long-term interest rates fall to historically low levels. The availability of foreign savings means that New Zealand’s investment does not have to be funded from domestic savings, resulting in a current account deficit and an inflow of foreign capital. There has also been an increase in banks’ willingness to lend to households through mortgages, with mortgages generally seen as a low-risk form of investment – mortgages are secured against houses, and the value of the loan is typically less than 100% of the value of the house, meaning the bank can generally recover the value of the loan in the case of default.

Real interest rates were also relatively low for a sustained period, although rates have increased in the past 12 months following a number of increases in the OCR.

Figure 14: Nominal interest rates

|

|

Source: RBNZ |

Figure 15: Real interest rates

|

|

Source: RBNZ |

These changes in interest rates have come during a period of financial deregulation. Financial deregulation has seen banks introduce new types of mortgages and relax the conditions they apply to borrowing. For example, Coleman (2007) notes that prior to deregulation, banks would generally not lend more than 75% of the value of a house, and imposed limits on the size of repayments relative to income, generally at 20–30%. Following deregulation and advances in technology, banks were prepared to lend 95% of the value of a house, mortgage repayment to income ratios were generally eased closer to 33% and the duration of mortgages was increased. In some cases, it is now possible to borrow 100% of the value of a new house.

Banks tend to express mortgage repayment to income ratios in nominal terms. As a result, for the same real interest rate, borrowers can borrow more in a low inflation environment because the nominal interest rate is lower and the mortgage repayment smaller. A combination of a higher mortgage repayment to income ratio, low nominal interest rates, and a lengthening of the repayment period, resulted in a large expansion in the amount households could borrow. Coleman shows how a household with an income of $50,000 could increase the amount they could borrow from $79,000 in 1989 to $191,000 in 2005.

Impact on demand

Financial deregulation helped put in place the conditions that have allowed households to borrow more through a gradual change in lending practices. Financial deregulation in isolation is likely to have had a relatively small impact on the demand for housing, however, the combination of deregulation, lower nominal and real interest rates and an increase in the global availability of credit has seen a large increase in borrowing capacity. This has encouraged people to ‘trade up’ their dwelling by buying a bigger and better house, adding to demand for housing and lifting prices. Interest rates began to increase from 2004 onwards, progressively reducing the importance of interest rates as a driver of increased demand for housing. Many of these factors have also played a part in driving house prices up in a number of other countries.

6.4 Economic growth, income growth and unemployment#

The current upswing in economic activity that began in 1998 is the longest period of economic growth in the past 30 years. During the house price boom, real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased 19.4% between December 2001 and June 2007.

The period of strong economic growth has been associated with rising employment and labour force participation, falling unemployment and increased income. At the start of the housing boom in December 2001, the unemployment rate was 5.4%. By September 2007, this had fallen to 3.5%. Over the same time period, total nominal income earned by wage and salary earners increased by around 40%, or around 25% in real terms.

The growth in income has been unevenly distributed, with the largest increases coming at the upper end of the income distribution and much smaller changes in real income occurring at the lower end of the income distribution. This topic is discussed in more detail in section 11.

Impact on demand

A lower unemployment rate is likely to have increased people’s confidence about future income and therefore their willingness to take on higher levels of debt. Rising real income, particularly towards the upper end of the income distribution, has increased the amount of money that people have for spending on houses and for servicing mortgage debt. In the future, rising incomes are likely to be associated with increased demand for housing, with more people likely to seek holiday homes or other second homes as they become wealthier. In the past, this trend has meant that increases in the stock of dwellings have exceeded household formation, with some of the dwellings not available for permanent accommodation. These factors have also played a part in driving house prices up in a number of other countries.

6.5 Expectations#

Rising house prices attracted people into the housing market, with an expectation that prices would continue to increase and a desire to enter the market before prices increased further. Coleman (2007) describes how expectations may not be formed rationally in circumstances where there are difficulties in making a well-informed prediction about prices.

Coleman suggests that when expectations are formed adaptively, prices and the number of transaction volumes in the market can diverge from fundamental or equilibrium values for an extended period of time. Willingness to purchase a house will depend on households’ financial circumstances, their expectations about average house prices and the suitability of the house. A demand shock may destabilise equilibrium patterns of prices and volumes, with the shock generating a change in reservation prices for sellers and expectations of future prices for buyers, leading to a long-lasting increase in prices.

Impact on demand

The demand shocks discussed elsewhere in section 6 may have induced a change in expectations of the future path of house prices. This is likely to have been one of the drivers of price increases, as well as a factor drawing investors into the market. Establishing the magnitudes of these influences compared with more fundamental drivers of activity is complicated. Econometric analysis by O’Donovan and Stephens of Westpac bank (2007) suggests that the fundamental drivers can account for most of the rise in house prices; however, a more recent update from Westpac suggests that prices may now be overvalued following recent interest rate increases.

6.6 Preference for property as a form of investment#

New Zealanders have a strong preference for houses as a form of investment due to the strong recent returns to housing and previous volatility in equity markets, such as the sharemarket crash of 1987. Estimates suggest that debt on rental properties has increased from around 21% of total mortgage debt in 1991 to around 33% in 2006, with debt on rental properties accounting for around 38% of the net increase in total mortgage debt.

Burns and Dwyer (2007) examined New Zealand households’ attitudes to various forms of saving and investment. They concluded that investment decisions and preferences are influenced by a number of factors, including:

- complexity, transparency and perceived past and future performance of different kinds of investment options

- a general lack of independent financial advice

- recent superior performance of property investment

- perceptions and personal tolerance of risk

- an often low level of financial literacy about products other than property

- personal or family experience of investment, a general wish to have control over the investment and trust in the advice of friends and family over unknown professional advisors.

6.7 Preference for home ownership#

Home ownership is an important aspiration for many New Zealanders because of the ability to personalise a property, the security of tenure and wealth accumulation benefits. Under existing commonly-used tenancy arrangements, tenants have limited tenure security and little capacity to personalise the property and treat it as their home. As a result, those households that want secure tenure need to buy a house. This does not increase the demand for the number of houses in New Zealand, but it does affect the demand for owner-occupied housing.

6.8 The tax system#

A number of elements of the New Zealand tax system directly affect the housing sector. This section discusses each of these factors.

Absence of taxation of imputed rent for owner-occupiers

If a household invests in, for example, a term deposit and rents a house to live in, the interest earnings on the term deposit are taxable. If the household uses their money to buy a house to live in, they receive an untaxed flow of housing services that is equivalent to the money that they would have paid to rent a similar property. This flow of services is often called imputed rent. Because imputed rents are not taxed, the tax system tends to favour more investment in owner-occupied housing and less in other types of assets.

The extent of this benefit to owner-occupiers depends on the level of equity held in the property. For owners who have debt, the payment of interest on the debt diminishes part of the benefit from imputed rents. The full benefit is captured by owners with 100% equity. The system therefore encourages the early repayment of mortgages and leads to a bias in the portfolio of households towards housing.

Non-deductibility of mortgage interest payments

A dollar paid off a household’s mortgage generates a return equal to the pre-tax mortgage interest rate. The same dollar invested in another asset with comparable earnings, which is subject to tax, would generate a return of the mortgage interest rate less whatever tax is payable. Any move towards making mortgage interest deductible without making imputed rents taxable would result in a substantial subsidy to highly-geared households (OECD, 2000).

Concessionary treatment of capital gains

New Zealand does not have a general capital gains tax. Consequently, no capital gains tax is applied to owner-occupied housing and, typically, no capital gains tax applies to rental property, unless the property was bought and sold with the intention of making a capital gain.[10] New Zealand makes a distinction between revenue receipts that are taxable and capital receipts that are not. The OECD (2000 and 2006) highlighted a number of adverse consequences arising from a failure to impose a comprehensive tax on capital gains, including a narrowing of the tax base and distortion of the allocation of savings and investment. The McLeod Review (2001) recommended against a capital gains tax because of the practical difficulties and the risks of high compliance costs.

Ability to deduct losses on investor rental housing

Like other businesses, a rental property investor can combine their net rental income with income from other sources. An investor’s total deductions for interest, rates, repairs and insurance may exceed the gross income from rent, creating a loss that can be applied to reduce the taxpayer’s liability on other sources of income. The value of this aspect of the tax system is directly related to marginal tax rates. Therefore, the increase in 2000 to a top marginal tax rate of 39% may have encouraged some additional investment in rental housing.

No GST on imputed or actual rents

Landlords do not charge Goods and Services Tax (GST) on rents but indirectly pay GST on the inputs used in providing the service, such as maintenance. Instead, New Zealand like other jurisdictions has opted, in the case of new dwellings, to apply GST at the time of the initial purchase of a property. This treatment should, at least in theory, have the same result in present value terms as applying GST to the rental flow from the property, with fewer serious practical issues. Applying GST to rents would also (in the absence of taxing imputed rents) drive a tax wedge between tenants of rental properties and owner-occupiers.

Depreciation allowances for investment properties

Depreciation is one of the expenses that a rental property investor can offset against other forms of income. The tax saving on depreciation is only a time-value-of-money saving as the tax on the depreciation component must be paid when the property is sold.

Local government rates

Rates are a form of taxes. Local government has discretion in setting the rates they charge in order to cover operating expenses. Grimes (2003) found that New Zealand has relatively light property taxes compared with many other developed countries. The OECD (2000) notes that the share of taxation revenue raised from property taxes (rates) in New Zealand is broadly in line with other countries and concluded that “property taxation is not acting as a significant barrier to the efficient use of land”.

Impact on demand for housing

The absence of tax on imputed rents favours home ownership over other investment options. In addition, the capacity for investors to deduct losses from rental properties against other sources of taxable income puts investors at a relative advantage to first home buyers (assuming they fund the property mainly through debt). Estimates prepared by the Unit, described in box 1, suggest that the ability to deduct losses from rental properties increases the value of a median-priced house to the investor by $25,000, relative to a potential home owner who needs a large mortgage to buy the same house.

Box 1: An illustration of the tax advantage to investors

This box shows the estimates of the Unit of how the tax system provides an advantage to rental property investors relative to owner-occupiers with similar levels of borrowings, by effectively reducing the interest rate they face by between 1.5 and 2.5 percentage points, depending on the level of gearing in the sector as a whole.

Table 4: Tax advantage of rental investment

|

A. Level of investor gearing |

0.33 |

0.33 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B. Total value of rental property ($bn) |

149.2 |

149.2 |

149.2 |

149.2 |

|

C. Interest rate |

7.5 |

10 |

7.5 |

10 |

|

D. Outstanding debt ($bn) |

49.2 |

49.2 |

74.6 |

74.6 |

|

E. Gross yield ($bn) |

7.3 |

7.3 |

7.3 |

7.3 |

|

F. R&M, ins, rates, deprecation ($bn) |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

|

G. Interest costs ($bn) |

3.7 |

4.9 |

5.6 |

7.5 |

|

H. Net return ($bn) |

-2.3 |

-3.6 |

-4.3 |

-6.1 |

|

J. Average loss per unit ($) |

-4,835.2 |

-7,367.9 |

-8,749.4 |

-12,586.8 |

|

L. Tax benefit at 0.3 marginal rate ($bn) |

-0.7 |

-1.1 |

-1.3 |

-1.8 |

|

M. Net return after tax ($bn) |

-1.6 |

-2.5 |

-3.0 |

-4.3 |

|

N. Interest costs less tax benefit ($bn) |

3.0 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

5.6 |

|

O. Effective interest rate (%) |

6.1 |

7.8 |

5.8 |

7.5 |

|

P. Implied subsidy to interest rare |

1.4 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

|

Q. Tax benefit as share of total value (capitalised at 10%) |

4.7 |

7.2 |

8.6 |

12.3 |

Notes

A. The Household Economic Survey (2001) shows investor gearing of 0.33. Since 2001 the size of the rental market has grown and it is likely that new investors have had higher than average gearing. For this reason 0.5 is also used.

B. Calculated from Statistics NZ estimates of the number of households living in private rental accommodation and REINZ median house prices.

C. Two different rates used to illustrate the range around estimates.

D. Row A* row C.

E. The gross yield is assumed to be 4.9%, then the $ return is calculated from row B *0.049

F. Assumed to be 4% of value of housing stock.

G. Row D* row C.

H. Row E – row F – row G.

J. Row H divided by rental stock.

L. Marginal tax rate assumed to be 0.3, could be higher if most rental investors are higher income earners. Benefit calculated as marginal rate*row H.

M. Row H – row L.

N. Row G + row L

O. Row C – row O.

Q. -1*((row L/0.1)*100)/row B.

Capitalising the average benefit per property suggests that the investor could pay $14,500–$37,000 more than a potential home owner who needs a large mortgage to buy the same house, with a mid-point of $25,000 being the best judgment of the Unit.

[8] A household is defined as one person usually living alone or two or more people usually living together and sharing facilities in a private dwelling

[9] The usually resident population, which does not include overseas visitors, increased 7.8% between 2001 and 2006. The Census night population count grew 8.4%, between 2001 and 2006.

[10] The test, in fact, refers to the property owner having at the time of purchase an intention to resell it.

7. Supply factors#

- The supply of new occupied dwellings has responded strongly to population growth, however, there are some signs of a shortage of supply in Auckland, particularly Manukau.

- The increase in new supply of occupied dwellings has come with large increases in the cost of constructing new dwellings since 2001, including increases in section prices, labour costs and the cost of materials.

- New dwellings are only a relatively small share of house sales.

7.1 Supply of dwellings#

Magnitude of the increase in dwellings

New Zealand does not have an annual survey of the size of the country’s dwelling stock. The Census provides a snapshot of the number of dwellings every five years. In between these years, Statistics New Zealand estimates the size of the dwelling stock based on the number of building consents that are approved, incorporating some assumptions about the number of consents that are not acted on and the number of deletions from the housing stock.

Housing supply can be slow in responding to changes in population because of the time taken to assemble the required mix of land, materials and labour; planning delays; and the time required to construct a dwelling. Growth in building consents and dwellings lagged behind the sharp population growth associated with net migration inflows during 2002 and 2003, however, by June 2003 consents for new dwellings reached 30,000 per annum and increased further to more than 33,000 in the year to June 2004, before dropping back to around 26,000 a year in the 2005, 2006 and 2007 June years. This represented a sizable step up in building activity from a historical average of around 20,000 building consents a year, and it shows a construction sector that is able to respond to rising demand and prices.

The net result of this strong increase in building activity was an increase in dwellings between the 2001 and 2006 Censuses of 125,000 dwellings. Around 110,000 of these were new occupied dwellings, with an increase of around 15,000 unoccupied dwellings. This large increase in dwellings is somewhat different to the experience of some other countries that have experienced house price booms, particularly the United Kingdom, where the supply response has been muted.

The critical issue examined by the House Prices Unit is whether the increase in supply has been sufficient to match the increase in the population. If not, then a shortage of houses would be expected to flow into higher house prices, higher rents and signs of crowding as more people are forced to live in a limited number of houses. This section also includes a discussion of the type of new dwellings that have been built.

A simple comparison of the growth in the total number of dwellings (8.1%) between the 2001 and 2006 Censuses compared with population growth (7.7%) does not point to any shortages at the aggregate level. A comparison between the growth in occupied dwellings (8.1%) and population and household growth does also not point to any shortages at the aggregate level.[11] This simple comparison could be misleading, for example, the regional distribution of dwelling and population growth is important, while the distribution of growth within the five year period could also be important.

The Unit has investigated two further approaches to address the question of whether the increase in supply has been enough to house the population growth. It is also important to consider the type of supply that has been added and which segments of the population have accessed the new supply.

Approach 1: Comparison of building consents and population growth

The first approach is to estimate the number of dwellings required to house the growth in the population, building in the following two assumptions:

- In the 2001 Census, the average household size was 2.6 per house. In the 2006 Census, the average household size was 2.7 people per house. The table calculates the number of houses required if average household size is 2.7 and if the ‘desired’ size was actually 2.5, in line with a declining trend over time.

- Building consent data is used to estimate the rate of construction of new houses, with an assumption that only 80% of new building consents translate into net additions to the country’s occupied housing stock. The remaining 20% is accounted for by consents not acted on, holiday homes and by activity that is replacing deletions from the housing stock.

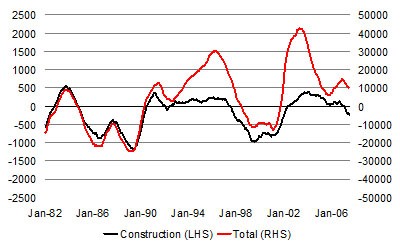

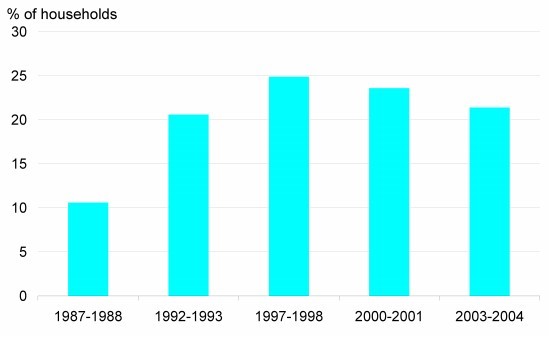

The table below shows the assessment of undersupply and oversupply resulting from this analysis. This provides an alternative approach to the simple comparison of Census numbers and sheds some light on the pattern of building between Census years.