Formats

Summary of Key Points#

- Cabinet has agreed to adopt a policy framework for regulating occupations. A copy of the framework is attached to this circular.

- All departments and agencies should follow the principles contained in the framework when dealing with matters relating to the regulation of occupations.

- If it is proposed to use an alternative approach than that provided by the framework, then the reasons should be explained in the proposal submitted to Cabinet.

- The Ministry of Commerce should be consulted on all occupational regulation proposals submitted to Cabinet.

Introduction#

1Cabinet agreed in 1998 to a package of policies put forward by an interdepartmental working group aimed at guiding the government's involvement in regulating occupations. The package includes:

- a policy framework on occupational regulation by government;

- the provision of examples of model legislation on occupational regulation as a resource for departments and agencies reviewing the occupations they regulate at present, or regulating new occupations;

- a requirement that the Ministry of Commerce be consulted on all proposals relating to occupational regulation.

Further details of these measures are provided in this circular.

Policy Framework#

2The aim of regulating occupations is broadly to protect the public from the risks of an occupation being carried out incompetently or recklessly. The policy framework agreed to by Cabinet requires those proposing regulation to identify the risks posed by a particular occupation and the best means of dealing with them. The solution will vary according to the occupation being considered but it will not always involve intervention by the government or legislation.

3A copy of the policy framework for occupational regulation agreed to by Cabinet is attached as Appendix 1. The framework:

- identifies the circumstances where occupational regulation is required to achieve protection of the public;

- defines methods of occupational regulation to fit particular situations;

- lists the principles and processes for effective occupational regulation by statute.

4Cabinet has agreed that all government departments and agencies should follow the principles contained in the policy framework in dealing with matters involved in regulating occupations. If it is proposed to adopt an alternative approach to that set out in the policy framework, then the reasons for this should be included in the proposal submitted to Cabinet.

Model Legislation#

5The Ministry of Commerce, working with the interdepartmental group on occupational regulation, has developed examples of legislative provisions for the different methods of regulating occupations as a resource document for departments. Copies of the resource document are available from the Ministry of Commerce on request.

6Each method outlined in the examples of legislative provisions covers a minimum level of regulation necessary to ensure both a fair process and consumer protection. The provisions are intended to provide a guide rather than a fixed approach. Departments and agencies may need to have additional provisions or make other changes to customise the model to meet the needs of the particular occupation they regulate. The model draws on existing examples and it is possible that over time alternative approaches will be developed.

Requirement to Consult Ministry of Commerce#

7Cabinet has also agreed that the Ministry of Commerce should be consulted on all proposals going to Cabinet or Cabinet committees which involve regulating an occupation, reviewing the way in which an occupation is regulated or altering some aspect of the regulation of an occupation. The Ministry should be consulted on the proposal at an early stage before submissions are finalised.

Further Information#

8Ministers' offices and Chief Executives should ensure that:

- all staff involved in regulating occupations or reviewing the way in which they are regulated, or proposing to change the regulation in some way are familiar with the advice in this circular and the policy framework on occupational regulation;

- any submissions for Cabinet and Cabinet committees on occupational regulation demonstrate that the policy framework has been considered in the formulation of proposals put forward.

9Copies of the policy framework are also available from the Ministry of Commerce in booklet form.

10Enquiries about the requirements in this circular should be directed to:

Kay Switzer or Sara Whyte

Competition and Enterprise Branch

Ministry of Commerce

PO Box 1473

Wellington

Marie Shroff

Secretary of the Cabinet

POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION BY GOVERNMENT#

Introduction#

1This policy framework is intended to guide government departments and agencies involved in regulating occupations. The framework:

- identifies the circumstances in which occupational regulation is required to achieve protection of the public;

- defines methods of occupational regulation to fit particular situations;

- lists the principles and processes for effective occupational regulation by statute.

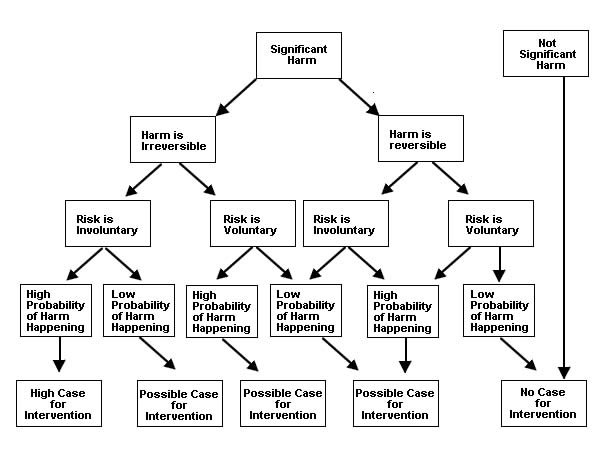

2The key decision points of the framework are summarised in Chart 1 and expanded in this paper.

Background#

Aim of regulating occupations

3The aim of regulating occupations is to protect the public from the harm that could be caused by incompetent, reckless or dishonest practice of an occupation. Occupational regulation can take several forms and can be carried out by the Government or by an occupational group or industry.

Types of occupational regulation

4General legislation affects the way in which occupations are carried out. This includes the common law, the criminal law and statutes such as the Consumer Guarantees Act. In addition, the Government regulates a range of occupations through specific legislation. The statutes and procedures vary from occupation to occupation but generally occupational regulation in statute is designed to protect the public from harm - either physical, mental or financial by:

- providing barriers to entry, such as particular qualifications and assessment of character;

- enforcing rules of practice and providing for disciplinary procedures;

- where clients’ money is involved, providing a form of insurance through bonds or similar devices; or

- requiring providers of services to disclose information that will assist consumers to assess the service.

| CHART 1: DECISION-MAKING PROCESS FOR GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT IN OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION |

|

STEP ONE: IDENTIFY WHETHER INTERVENTION IN AN OCCUPATION IS NECESSARY

If significant irreversible harm is likely there is a case for intervention in the practice of the occupation. |

|

STEP TWO: IDENTIFY WHETHER INTERVENTION BY GOVERNMENT IS JUSTIFIED

If significant harm is likely, existing means of protection are insufficient, the industry is unable to regulate itself adequately and intervention by Government is likely to improve outcomes, there is a strong case for Government intervention. |

|

STEP THREE: IDENTIFY THE MOST EFFECTIVE FORM OF GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION

|

If only a specific aspect of the practice of an occupation poses a threat to consumers or third parties, the best solution is to target that aspect rather than legislate to regulate the occupation.

STEP FOUR: IF LEGISLATION IS REQUIRED TO REGULATE AN OCCUPATION WHAT FORM OF REGULATORY REGIME IS NEEDED?

- disclosure

- registration

- certification

- licensing those entering an occupation

Licensing workers in an occupation imposes costs and reduces flexibility more than other means of control and should be reserved for occupations where there is a high need for control for safety reasons. Any of the other methods are likely to be adequate control for occupations, which do not affect health or safety.

STEP FIVE: WHAT LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS ARE NEEDED TO REGULATE OCCUPATIONS?

(Refer to model legislation for examples of best practice regulation for the different types of regulatory control)

THE POLICY FRAMEWORK#

ASSUMPTIONS BEHIND THE FRAMEWORK

5The framework assumes that:

- intervention by Government in occupations should generally be used only when there is a problem or potential problem that is either unlikely to be solved in any other way or inefficient or ineffective to solve any other way;

- the amount of intervention should be the minimum required to solve the problem;

- the benefits of intervening must exceed the costs.

STEP ONE : WHEN IS INTERVENTION IN AN OCCUPATION NECESSARY?

6A key trigger for intervention being necessary is whether there is a possibility that incompetent service by members of the occupational group could result in significant harm to the consumer or a third party. Nearly all occupations have the capacity to cause harm that is not significant. However, given the compliance costs of intervening in occupations, it is important to limit intervention to cases where the harm has the potential to be significant.

7Significant harm is defined as covering significant harm to one person or moderate harm to a large number. Moderate harm to a large number might arise from one event or from the aggregated actions of different providers of a service.

8Significant harm that is irreversible (such as permanent disability) is more likely to justify intervention than reversible harm (such as moderate food poisoning).

NATURE OF RISK

9The need for intervention depends upon the nature of the risk of significant harm from the incompetent performance of an occupation.

10Risks may also be voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary risks are those that the public generally know about (or could be expected to know about) and therefore avoid or control. For instance, deep sea diving is a voluntary risk, while working in a building that does not meet basic safety standards is an involuntary one.

11There is a possible case for intervention where there is a risk of significant harm, the harm is irreversible and the risk involuntary but there is a low probability of the harm occurring. Similarly there is a possible case where the harm is reversible but the probability is high. There is also a possible case where the harm is reversible and the probability of harm occurring is low but the risk is an involuntary one.

12There is a possible case for intervention when the risk of significant harm is highly probable, whether the risk is voluntary or involuntary and whether the harm is reversible or irreversible.

13Chart 2 illustrates the relationship between the type of harm and the nature of risk and the case for involvement in regulating an occupation. Note that while this framework contains high level principles about the nature of risk and when intervention is justified, concepts such as “significant harm” cannot be defined with precision and may mean different things under different circumstances. The broad principles in Chart 2 need to be applied in the light of the particular circumstances relating to an occupation.

Chart 2: WHEN THERE IS A CASE FOR INTERVENTION IN AN OCCUPATION

Note: (*)"Significant Harm" covers significant harm to an individual and/or moderate harm to a large number of individuals

STEP TWO : INDUSTRY OR GOVERNMENT REGULATION?

14There are potential advantages and disadvantages from having an industry body control entry and other aspects of occupational regulation as opposed to having government involvement:

- an industry body would have expert knowledge, but potentially stands to gain monetarily by restricting entry to an occupation;

- a government agency may lack the relevant industry knowledge and may be apt to be more inefficient than an industry body. However it may have advantages in terms of impartiality. There is a need to consider these trade-offs when deciding on the most appropriate form of regulation.

INDUSTRY SELF-REGULATION

15Industry or occupational groups have means to regulate themselves including:

aCodes of practice: Members of an occupation can agree to impose upon themselves codes of conduct or practice with the aim of providing benefits to the consumer and/or protection from harm that could be caused by members of their occupation. For example groups can establish agreed standards of training, rules that regulate behaviour in the workplace (such as safety procedures), processes for monitoring the performance of their members, and dealing with complaints. (For example the Advertising Standards Authority, in association with the media, maintains a code of acceptable standards of advertising and a complaints and disciplinary process which advertising companies agree to abide by).

bVoluntary accreditation systems: Businesses or practitioners can seek accreditation but a failure to be accredited does not prevent them carrying out their business. The occupational group concerned decides upon the requirements. These may include particular qualifications or bond arrangements and may specify different levels of accreditation. This system gives the public information about the quality of the service without restricting entry to the occupation. For instance the Master Builders Association operates an accreditation scheme. Members of this are marked out as likely to provide superior quality work. In addition, membership provides assurance to the customer that complaints will be dealt with by a third party, and financial losses made good through the Association.

16Members of occupational groups often have strong incentives to self-regulate. In addition to avoiding harm to users of their service they also want to maintain the good standing of their occupation with the public, and to promote it.

17Some occupations use combinations of the means of self-regulation outlined above and some have self-regulation processes, which are backed up by legislation.

CASE FOR GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION

18The strength of the case for Government rather than industry intervention depends upon a combination of the nature of the harm that could occur from incompetent, reckless, or incomplete provision of a good or service from an occupational group, and the availability of means other than Government intervention to avert or remedy any harm.

19Government (rather than industry) intervention would generally be required when:

- significant harm to consumers or third parties is possible; and

- existing means of protection from harm for consumers and third parties are insufficient, and

- intervention by Government is likely to improve the outcomes; or

- there is market failure which industry cannot remedy; or

- the industry is unable to regulate itself because of the costs involved.

STEP THREE : MEANS OF OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION BY GOVERNMENT

Non-statutory means

20The Government has means other than occupational regulation by statute to reduce the risk that services provided by members of an occupational group may harm consumers or third parties. These are:

aInformation provision: The Government can produce information for the public to make consumers aware that some services provided by occupations, if performed incompetently or dishonestly, could pose a risk. Information may also be provided to assist consumers to choose competent practitioners and be aware of the remedies available to them through consumer legislation. Information may also be provided through legislation, which compels people providing a service to disclose relevant information to the customer.

bTraining: Government funds training and provides the means of assessing training to ensure that members of an occupational group are trained to a sufficient level to carry out their tasks competently and safely.

cProvision for setting and enforcing standards: Rather than regulating a whole occupation, some legislation, for example the Health and Safety in Employment Act, makes provision for safety standards and codes of practice to be established for particular tasks. Such legislation also provides for inspection by Government agencies and for penalties to be imposed for non-compliance.

dAs a major employer and purchaser of services: Where the Government is the major employer of members of an occupation group (such as for nurses or probation officers) it can specify the standards it requires practitioners to meet. The Government can also choose to purchase (or subsidise) only those services provided by practitioners who meet pre-defined standards, such as having particular qualifications. (For instance reimbursement of treatment costs through ACC is made only to providers with particular qualifications).

21When the use of these methods is more likely to be effective than regulation of an occupation by statute depends upon the nature of the problem to be solved. For instance, if the problem is that consumers do not have enough knowledge to pick competent practitioners the answer may lie in the option described in paragraph 20(a). When there is no assurance of quality of providers the answer may lie with setting up training as in the option in paragraph 20(b). Where some, but not most, of the tasks carried out present a hazard, the option in paragraph 20(c) might work best.

STEP FOUR : TYPES OF GOVERNMENT OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION BY STATUTE

22The main types of control Government exercises through occupational regulation legislation and

- requiring disclosure of information about the service or the service provider (Disclosure);

- requiring practitioners to identify themselves in a public way (Registration);

- distinguishing particular types of service from others through protecting titles (Certification);

- restricting some tasks to particular members of an occupation (Licensing tasks) ;

- controls on entry to the occupation (Licensing).

aDisclosure: Providers of a service are required to disclose specified information to prospective users of the service. For instance investment advisers must provide information about how they handle investors’ money, what records they keep, and whether they have been convicted of a crime of dishonesty in the previous five years. Disclosure is used where the threat is to individuals’ finances and customers have a choice of whether to use a particular service or not.

bRegistration:1 Service providers give their names and addresses and pay a fee. Registration is usually used where the threat to public health, safety or welfare is minimal. There are no restrictions to entry to the occupation apart from the requirement to be on the register if you wish to enter, or continue to practise, a particular occupation. Registration does not convey any suggestion of competence or quality of service. It has administrative benefits, such as providing a means of identifying practitioners so information can be provided to them and it may be used to enforce other legislation. (For example, having a register of secondhand dealers may assist the police in investigating thefts).

cCertification: An agency is empowered by statute to certify to the public that individuals have satisfied particular requirements that indicate their competence in a particular field. The certified practitioner is given the exclusive right to use a certain title, for instance, “Registered Psychologist” or “Chartered Accountant”. Those who are not certified can offer their services in competition with certified practitioners but under a different title. Certification provides information to the public by giving assurance that the practitioner has met certain requirements at the point of certification. It does not deal with the quality of the work done or the competence of the practitioner once the person has been given the right to use the certified title, except that certification is usually accompanied with disciplinary processes aimed at providing a means of removing the right to use the protected title if the practitioner falls below the standards acceptable to the regulating body.

dLicensing tasks: This involves enacting legislation to grant an exclusive right to perform certain tasks to defined groups of people. For instance, only registered medical practitioners, dentists and veterinarians may prescribe drugs. Regulation of this kind is generally used where poor performance of a particular task (eg. administration of drugs and anaesthetics) is likely to impose severe costs on consumers or where the government wishes to control who is to carry out certain functions for the state (such as certifying deaths for example).

Licensing of tasks is more flexible than licensing members of a particular occupation and leaves some scope for multi skilling. It reduces competition less than licensing of workers because the restrictions relate to only part of the job. The intervention is transparent. However, the specification of tasks and occupations is time-consuming and quickly outdated as occupational practice changes. There are enforcement problems, especially where the service is only part of a broader service, as it is difficult to know when a person not licensed to do so has carried out a restricted service. (This has been found to be particularly the case where it is used to cover some forms of treatment used by psychologists).

eLicensing workers in an occupation: This regime explicitly prohibits all but licensed persons from offering certain services. Entry to the occupation is dependent upon the worker meeting prescribed standards. Entry qualifications normally involve education and some discretionary criteria related to character or fitness to practice. (For example taxi drivers are licensed following an examination on their knowledge of their area and a police check to ensure that they are a “fit and proper person” to operate a taxi).

Licensing of workers is the least flexible form of occupational regulation as those not meeting the entry requirements are unable to practice. It minimises the risk to the public from unskilled practitioners by requiring that all who practice have met particular standards on entry but it does not usually deal directly with the continuing relevance of those standards or the current competence of workers after they are licensed. (There are some exceptions to this. For example, people licensed under the Electricity Act are required to undertake refresher training on safety procedures to maintain their knowledge in this area).

As with certification, a disciplinary process exists which may result in transgressors having their licence suspended or removed.

Where the licensing is primarily within the control of the occupational group the group has incentives to increase the barriers to entry by raising the standards required. This means that there is less competition to existing members of the group and this enables higher prices to be charged.

Licensing reduces public search costs but can reduce consumer choice as there are limits on the range of practitioners able to provide a particular service and there is less incentive on licensed practitioners to distinguish by differing levels of quality and service. While there may be competition within the occupation, it is restricted to competition for a limited and specific range of services.

WHICH FORM OF OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION THROUGH STATUTE IS MOST APPROPRIATE IN A GIVEN CASE?

23Which type of regulation is most appropriate to a particular occupation depends upon whether there is a problem if entry to that occupation is not restricted, the nature of the problem, and the availability of other means to solve the problem.

24Because restricting entry to an occupation through licensing workers imposes costs and reduces flexibility more than any other means of intervening in the conduct of an occupation, it should be reserved for cases where the conduct of an occupation could pose a significant risk of harm, self regulation by industry will not work and other means of intervention by Government will not solve the problem. There is, however, justification for using this method of occupational regulation where the occupation has potential to cause significant harm and the practitioner is a sole operator or works independent of supervision, for example medical workers in the field, or taxi drivers. (Those working for an employer have additional disciplines applied in the form of another person being accountable for their actions and the employer is also able to provide quality assurance and training, and monitor performance).

25Where regulation is justified and significant harm is not involved, the use of certification with protection of title can be sufficient regulatory control. This provides information to the public about the quality of service and the qualifications of those using the protected title but it also enables those not meeting the requirements to carry on the same business as long as they do not mislead the public into thinking that they have the qualifications necessary to use the protected title. This is the model used in the Institute of Chartered Accountants Act 1996.

26Questions for policy makers to ask in considering the appropriate type of regulation are:

- Will significant harm be caused to users of the services of an occupational group (or third parties) if entry to the occupation is not restricted?

- What requirements are in place to protect the public from potential harm from members of this occupation? (These may include placement of liability on an employer in the Health and Safety in Employment Act or general consumer protection legislation.)

- Would certification (title protection) be sufficient to regulate the occupation?

- Are there particular circumstances for the practice of a particular occupation which require restricted entry to the occupation or the restriction of particular tasks?

- Will the benefits of having a particular regulatory regime outweigh the cost of the intervention?

- Are there international regulatory requirements affecting the way this occupation can be regulated?

- Are there circumstances, which would make intervention by Government rather than industry necessary or appropriate?

STEP FIVE : HOW SHOULD OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION BY GOVERNMENT BE DESIGNED AND IMPLEMENTED?

27Regulation should be guided by the following general principles drawn from the Code of Good Regulatory Practice approved by Cabinet in 1997. These are:

- effectiveness: Occupational regulation should be designed to minimise an identified risk of significant harm to consumers or the public from market failures, such as information asymmetries and externalities in service markets.

- efficiency: Taking into account alternative approaches, the benefits of occupational regulation to society (consumer and public protection) should exceed the costs of occupational regulation to society (eg. higher prices and reduced competition).

- equity: Occupational regulation should be fair; it should treat individuals in similar situations similarly and individuals in different situations differently.

- transparency: In formulating and administering occupational regulation, the process should be transparent to both the decision-makers and those affected by those decisions.

- clarity: Occupational regulatory processes and requirements should be as understandable and accessible as practicable.

- institutional: Occupational regulation should minimise the incentives for regulatory bodies to provide occupational protection rather than public protection.

28An important additional point is that any regulation should be able to be enforced effectively.

SPECIFIC ADDITIONAL FEATURES NEEDED IN OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION REGIMES

29Agencies designing or reviewing regulation of an occupation should incorporate the following features as far as possible:

aFor disclosure regimes:

- the information required should be tailored specifically to the potential problem posed by incompetent, reckless or corrupt practice of an occupation.

bFor registration regimes:

- absence of restrictive criteria such as restrictions on age and ownership and residence (except where there is a demonstrable need);

- criteria for refusing registration and means of review of decision are explicitly stated.

cFor certification regimes:

- separation of disciplinary functions from those to do with providing services to members;

- significant consumer participation in setting entry standards and discipline;

- clear statement of the certifying body’s purpose and functions;

- the certifying body should have responsibility for providing for the ongoing competence of members of the occupation;

- there should be provision for full disclosure of information on processes and on decisions of the certifying and disciplinary bodies;

- admission criteria should be based on relevant and objective data to ensure fair and consistent treatment of applicants (eg. criteria such as age and residence are probably not appropriate and any judgements on a person’s suitability for an occupation need to have an objective basis);

- any regulation must operate in an impartial manner.

dFor licensing regimes:

- separation of disciplinary functions from those to do with providing services to members;

- significant consumer participation in setting entry standards and discipline;

- clear statement of the governing body’s purpose and functions;

- the governing body should have responsibility for ongoing competence of members of the occupation;

- provision for flexibility eg. detailed entry requirements should not be set in legislation, nor matters of administration require Ministerial approval;

- disciplinary bodies should have fair and transparent processes and access to the full range of sanctions including fining, suspending and de-licensing transgressors;

- admission criteria should be based on relevant and objective criteria to ensure fair and consistent treatment of applicants;

- obligations, standards and sanctions should be designed in such a way that they can be imposed impartially and consistently;

- there should be provision for full disclosure of information on processes and on decisions of the licensing and disciplinary bodies involved.

30The need for regulation and the most effective regime for it, should be periodically reviewed to ensure that the regime in place continues to meet its intended objectives with minimal negative impact on competition and consumer choice.

IMPLEMENTING THE FRAMEWORK

31Cabinet has agreed that this framework should be adopted as a way of promoting a more rational and consistent approach to Government’s intervention in occupations. Departments and agencies reviewing occupations or proposing new occupational regulation are required to consider the questions raised in the framework and to observe the principles and processes outlined in it. Where a department or agency wishes to take an approach which deviates from the principles or processes put forward in the framework, it is required to formally explain in its policy proposal why the approach proposed is better.

32The requirement for agencies proposing occupational regulation to consult with the Ministry of Commerce provides the opportunity for the need for regulation and the most appropriate type to be considered and for the operation of the framework to be monitored and improvements made as required.

OCCUPATIONAL REGULATION LEGISLATION

33Once a case has been established for occupational regulation by legislation, use of a generic template for legislative provisions which incorporates the principles and processes in the framework and best practice occupational regulation would increase the chances of an effective and consistent across-Government approach to occupational regulation. A set of examples of model legislative provisions for the main forms of occupational regulation - registration, licensing, disclosure and certification regimes - and the processes relating to them is available from the Competition and Enterprise Branch of the Ministry of Commerce.

1Note that registration as a term is commonly confused with more restrictive types of occupational regulations because of the widespread use of terms such as "Registered Nurse". Strictly speaking nurses are licensed not registered.